One room in the exhibition "Michael Armitage. Paradise Edict" presents East African painters that are thus key acteurs within the articulation of East African Modernism, and as such have significantly shaped Michael Armitage as an artist. We introduce those artists and their works on the Blog.

In his paintings the young British-Kenyan painter Michael Armitage combines East African and European motifs and painting traditions. The iconography of Titian, Francisco de Goya, Édouard Manet, Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh and Egon Schiele can be found in the works’ compositional elements, motifs and color combinations. The artist’s palette and symbolism are equally inspired by East African artists, to whom a separate room is dedicated as a kind of homage in the Haus der Kunst presentation.

The room “Mwili, Akili na Roho” (“Body, Mind and Spirit”) in the exhibition presents East African figurative painters that are thus key acteurs

within the articulation of East African Modernism, and as such have

significantly shaped the visual thinking of Michael Armitage. The

collection of works is demonstrating insightful aesthetic and

thematic ties with Armitage’s work and locating his practice within

a historical dialogue with the preceding generation and the art history

of the region.

Meek Gichugu

*1968 in Nairobi, Kenya

Meek Gichugu was part of the so-called Ngecha Group which was comprised of artists such as Sane Wadu, Eunice Wairimu, Lucy Njeri, Wanyu Brush, Francis Kahuri, and Sebastian Kiarie. Inspired by this creative atmosphere, Gichugu started his artistic journey in the early 1990s. His breakthrough came already in 1991 when he was given a solo exhibition at Gallery Watatu in Nairobi, where his art received both critical and public acclaim. The subjects of Gichugu’s unsettling work inhabit a world in which the familiar jockeys for space with the sinister resulting in extraordinary surrealist groupings: exotic fruits, strange animals parading across the canvas, distorted human figures, hidden and open sexual symbols. A recurring narrative device in Gichugu’s work is the metamorphosis of humans and animals. This refers to traditional Kenyan beliefs where animals take on human characteristics and humans behave in animalistic ways.

Jak Katarikawe

*1938 in Kigezi, Uganda

† 2018 in Nairobi, Kenya

Jak Katarikawe is an Ugandan artist who lived most of his life in Kenya and is one of the best-known painters of East Africa. He began as a self-taught artist but came into close contact with the Makerere School of Fine Arts in Kampala in the 1960s and 1970s. Quite early on, his paintings gained international popularity and due to his impressionist style he was sometimes called the “Chagall of Africa.” His very personal and emotional works tell everyday stories about life, as well as the traditions and customs of his home region of Kigezi in south-western Uganda. Animals, landscape, family, marriage, love, and sexuality are recurring motifs and themes. Although he lived in Kenya for the majority of his artistic career, it is clear through his dreamy paintings that he predom- inantly reflected ideas stemming from his experiences as a herdsman in Kigezi. Besides painting, Katarikawe also worked with black-and-white prints. Beginning in 1966, he partici- pated in numerous international exhibitions. His solo show, Dreaming in Pictures: Jak Katarikawe (2001/2002) was first presented at the Weltkulturen Museum in Frankfurt am Main, before travelling to the National Museum of Kenya, Nairobi, and the Makerere Art Gallery in Kampala, Uganda.

George Lilanga

*1934 in Kikwetu, Tansania

† 2005 in Dar es Salaam, Tansania

Tanzanian painter and sculptor George Lilanga belonged to the Makonde tribe and lived in Dar es Salaam. He was the first to adopt the shetani forms of tra- ditional Makonde carving and add color to them, both in paintings and onto the sculptures themselves. Lilanga’s compositions shed insights into the at- mosphere of life and work in Tanzania. His work circles around portrayals of African solidarity and community. He exhibited in several countries and prestigious institutions such as the Centre Pompidou in Paris, and the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao. His works are included in leading international col- lections like the Contemporary African Art Collection, based in Geneva.

Makonde

Makonde sculpture derives its name from the Makonde tribe, which lives in Mozambique and Tanzania. Makonde carving is an old cultural technique passed down from generation to generation. Traditionally, the carvers used the dark brown, almost black wood of the mpingo tree, also known as African Blackwood, which is found across the dry savanna region of East Africa. Makonde sculptures are characterized by their depictions of shetani (mis- chievous spirits of the unseen world). These figures are often part-human, part-animal, and part-spirit, and regularly take the form of long, thin limbed figures interlinked in complex, outlandish poses.

From the 1950s onward, Makonde carving underwent a renaissance. Outstanding Makonde artists moved to the metro- polis Dar es Salaam in Tanzania, where their wood carving became internationally known. Individual artists developed their own characteristic styles, sometimes using new motifs. Today, many Makonde sculptures can be found in international collections of contemporary art. In addition, Makonde carving has discovered a lucrative market among tourists. As with Tingatinga painting, mass-produced imitations of Makonde sculpture are sold as souvenirs.

Peter Mulindwa

*1943 in Bunyoro, Uganda

Ugandan artist Peter Mulindwa studied at the Makerere School of Fine Art in Kampala from 1967 to 1971, majoring in painting. In the 1970s and 1980s, he was active as an artist and, even though his interests were in local spirituality and magic, he staunchly criticized corrupt Ugandan leaders through anecdotes in his art. His etching African Fable (1970) depicts a large number of animals that do not appear in their natural habitat and interact like human beings. Depictions of animals engaging in conversation, either with themselves or with humans, and humans with animalistic features are common in many Ugandan folktales, to which the artist refers.

Theresa Musoke

*1944 in Kampala, Uganda

Theresa Musoke is an Ugandan artist who, in 1965, became the first woman to have a show at the Uganda Museum in Kampala. This was shortly after she had completed her degree at the Makerere School of Fine Arts in Kampala and received a scholarship for the Royal College of Art in London. Today she is considered one of the most significant Black woman painters in East Africa with an uncompromising attitude towards the male-dominated world around her, specifically in Kenya (1974-96) and Uganda, where she is currently based. In many of her works she explores the symbiotic relation- ships between the living world and its environments. Musoke’s paintings create mercurial visions in which the outline of one form often describes the beginning of another, and the points at which figures within a landscape begin and end is not obvious. The effect is a fluid, interdependent world of figures, animals, and their surroundings. Besides teaching at several universities and art institutions in Kenya and Uganda, Musoke is also celebrated for pioneering social change in her home country.

Asaph Ng’ethe Macua

*1930 in Karura, Kenya

The career of Kenyan artist Asaph Ng’ethe Macua spans more than six decades. One of his artworks (Asaph Ng’ethe Macua in a Hospital Bed, n.d.) included in this exhibition shows the fragility of the human body. The work refers to his life-long struggle with illness, especially in the 1950s when he lost a part of his lung and was forced to stay in the hospital for 5 years. Despite a difficult youth marked by poor health and poverty, Macua managed to study at the Makerere School of Fine Arts in Kampala and devote his life to art. In 2019, he published his autobio- graphy From Misery to Joy, in which he writes about his story of persistence and strength despite the continued challenges which he faced. The book launch was accompanied by a retrospec- tive at the National Museum of Kenya and showed works from as early as the 1940s.

Elimo Njau

*1932 at Mount Kilimanjaro, Tanzania

Elimo Njau is a well-known Tanzanian artist and cultural entrepreneur who lives in Nairobi. He studied at the Makerere School of Fine Arts in Kampala. Njau believes that art and faith are inseparable. At the 1962 International Congress of Africanists in Ghana he declared his belief in the existence of the “true Africanist” in art, and in general: “By true Africanists, I mean African artists embracing the ideology of the living God and His creative power through the minds, souls and the bodies of real people in present Africa.” Besides his painting, Njau has created many works for public buildings in Kenya, Tanzania, and Uganda. In addition to his artistic work, he is acclaimed for his commitment to the art scene in East Africa. He founded the Paa-ya-Paa Art Gallery (1965-1998), which was the first African-owned art centre in East Africa, a forum for contemporary art, hosting performances, evening debates, and workshops alongside exhibitions.

Magdalene Odundo

*1950 in Nairobi, Kenya

Kenyan-born Magdalene Odundo is one of the world’s most esteemed ceramic artists. Her practice started in the early 1970s after relocating to the United Kingdom. She studied at the Cambridge School of Art and the Royal College of Art in London. Her works are inspired by the human body and the way it can contort into many positions. Odundo’s highly finished, smooth, and shimmering vases often grow from a spherical base to expand into a cylindrical mold which eases into a carved narrow. Her works are included in the collections of numerous inter- national institutions, among them the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; the Victoria and Albert Museum, London; and the British Museum, London.

Chelenge Van Rampelberg

*1961 in Kericho, Kenya

Born and raised in Kericho, Kenya, Chelenge Van Rampelberg currently lives and works on the border of the Nairobi National Park. She is considered the first female sculptor of Kenya. Van Rampelberg may not have received an academic art training, but her early years were filled with indigenous artistry. The types of woods she works with are diverse, she sculpts using everything from doum palm, ebony, and jacaranda, to avocado and sikotoi. The grains, colours, textures, and types of woods are of great importance, deeply rooting her artistic vision in indigenous Kenya.

Edward Saidi Tingatinga

*1932 in Tunduru District, Tanzania

† 1972 in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

Edward Saidi Tingatinga was a self- taught painter who was born in southern Tanzania on the border of Mozambique and moved to Dar es Salaam in 1955. There, he worked as a domestic ser- vant for a colonial administrator. Tingatinga developed an admiration for painting and started experimenting with the medium in his mid-thirties. On squares of chipboard he mainly painted pictures of animals against plain backgrounds or in imaginary landscapes. A simple, almost childlike style is characteristic of his work. Tingatinga emphasized contours and decorated certain parts of the animal’s body. He painted using glossy house paint, which gives his works their vibrant richness. The clarity of his painterly vocabulary quickly became popular, especially among Western tourists. Tingatinga tragically died at the early age of forty, mistakenly shot by police. But in these few years he already gained many followers who imitated his style to such an extent that today people refer to Tingatinga painting as an artistic movement.

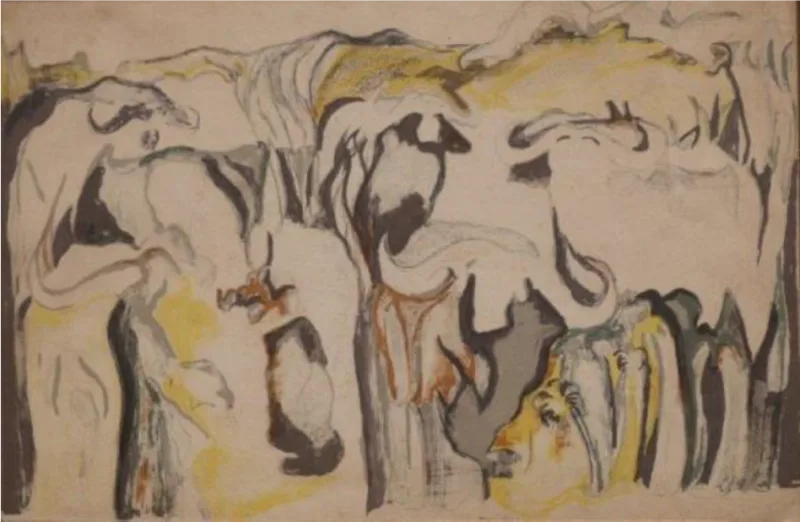

Sane Wadu

*1954 in Nyathuna, Kenya

Sane Wadu is a Kenyan artist, who aban- doned his birth name, Walter Njuguna Mbugua, in order to mock critics who, in response to this expressionist paintings, questioned his sanity. The self-taught artist, who initially worked as a teacher and court official started painting professionally in 1984 and is well known for his abstract way of painting. Some of the themes explored in his works include politics, gender, social injustice, as well as biblical subjects. While Wadu was primarily concerned with the animal world in his early work, he increasingly devoted himself to the human figure. His style is expressive; in his earlier period characterized by thin washes of gouache on paper and later developing into thick, impasto applications of paint and quick brush strokes. From the late 1980s onwards, his work has been featured in various international group and solo shows within Africa, Europe, and the United States.