The question of cosmopolitanism in today's society has acquired a new urgency through the strengthening of right-wing, conservative, and nationalistic tendencies. In her essay Anna Schneider investigates the concept as well as the current discourse and creates a reference to the works of the four artists in the exhibition „Interiorities“.

At first glance, Njideka Akunyili Crosby, Leonor Antunes, Henrike Naumann, and Adriana Varejão are four artists with very little in common. They come from distinct regions of the world, belong to different generations, work in diverse media, and express themselves in divergent visual idioms. Moreover, the stories these artists address within their works emerge from disparate temporal and geographic contexts. Nonetheless, as the exhibition “Interiorities” argues, all four share a central concern, namely the significance of cosmopolitanism in contemporary society and thus of a worldview that perceives itself as being related to, in dialogue with, and ultimately responsible for all forms of existence. With a pronounced awareness of history, these artists highlight the individual’s interwovenness with the world as a central challenge of existence. Through this group exhibition, it becomes clear that the concrete objects found in interior spaces function as spatially manifested extensions of the individual and of her own inner mental world. The interior mirrors the colliding interconnections involved in the sense of identity, of belonging and separation, of our entanglement in history and societal visions of the future, and of inwardly oriented nationalism and culturally receptive cosmopolitanism.

The idea of the cosmopolitan

The concept of the cosmopolitan first emerges in the fourth century BCE among the Cynics, who understood themselves – in contradistinction to the notion that every individual belongs to one among various communities – as free citizens of the universe. Ever since, the philosophical-political term “cosmopolitanism” (from the Greek κόσμος (kósmos), meaning “world order, order, or world,” and πολίτης (polítes), meaning “citizen” or literally one of a city/πόλις) has experienced an eventful history involving attributions of meaning and attempts at delimitation, at whose core resides the conviction that it is not so much nationality, race, or gender that determines the identity of an individual, but rather an affiliation with the totality of the world. The concept of the cosmopolitan therefore differs radically from that of provincialism and nationalism, as well as regionalism. At the same time, it must be distinguished from the concept of globalization, which primarily characterizes economic realities. Nonetheless, we must of course recognize that the spatial, technological, and economic globalization of the world multiplies the number of relationships of each individual and their complexity.

Current discourse on cosmopolitanism

In the current discourse on cosmopolitanism in cultural studies and philosophy, in which thinkers such as Arjun Appadurai, Kwame Anthony Appiah (“Making Conversation”), and Paul Gilroy (After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture?) are actively involved, the notion of the invitation to dialogue stands in the foreground, as the central forum for a confrontation with the challenges resulting from the collision between particular and universal interests.

Meanwhile, the discussion about the concept of cosmopolitanism has acquired a new urgency through the strengthening of right-wing, conservative, and nationalistic tendencies which advocate for an explicitly anti-cosmopolitan attitude. Right-wing conservatives lament the formation of “urban elites” whose connection to their respective homelands is said to be “weak” and who are contrasted with the narrative of those “left behind.” (Alexander Gauland: „Warum muss es Populismus sein?“, FAZ am 6. Oktober 2018. For a critical commentary by Bodo Mrozek, see „Kultur, gut?“, in: Die ZEIT, Nr. 44/19, 25. Oktober 2019 - To the article). That this line of argumentation is already dangerously close to the rhetoric of the National Socialists and Stalinists, who spoke of the “rootless cosmopolitan” (an allusion to their anti-Semitic agendas) is readily evident.

In a speech delivered early last year, for example, Alexander Gauland takes up the thesis, formulated by David Goodhart, of the rootless “Anywheres” who dominate cultural life, the sedentary, less educated, and hence left-behind “Somewheres,” and the “In-betweens,” who are not discussed further. That this schematic subdivision, which equates a cosmopolitan worldview with membership in an urban educated, jet set, or hipster elite, actually falls short is demonstrated by Bodo Mrozek through references to transcultural popular culture. He rebuffs the argument by referencing the example of the reception history of American jazz in postwar Germany, which was primarily embraced in the 1950s by people with little formal education. (Bodo Mrozek: „Das populäre Feindbild der ‚kosmopolitischen Eliten‘“, in: Deutschlandfunk, 29. September 2019 - To the article) Similarly, Arjun Appadurai speaks of a cosmopolitanism “from below”: “Nevertheless, what I call ‘cosmopolitanism from below’ has in common with the more privileged form of cosmopolitanism the urge to expand one’s current horizons of self and cultural identity and a wish to connect with a wider world in the name of values which, in principle, could belong to anyone and apply in any circumstance. This vernacular cosmopolitanism also resists the boundaries of class, neighborhood and mother tongue, but it does so without an abstract valuation of the idea of humanity or of the world as a generally known or knowable place.” (Arjun Appadurai: „Cosmopolitanism from Below: Some Ethical lessons from the Slums of Mumbai“, in: The Salon, Band 4)

Cosmopolitanism in the exhibition "Interiorities"

But what does this have to do with the artwork by these four artists brought together in the exhibition? Their works manifest a preoccupation with the challenges and aspirations associated with a cosmopolitan attitude. Manifest in them are both the historical tensions which persist in the present as well as the potential harbored by the ethical, social, and cultural vision of a planetary consciousness of solidarity.

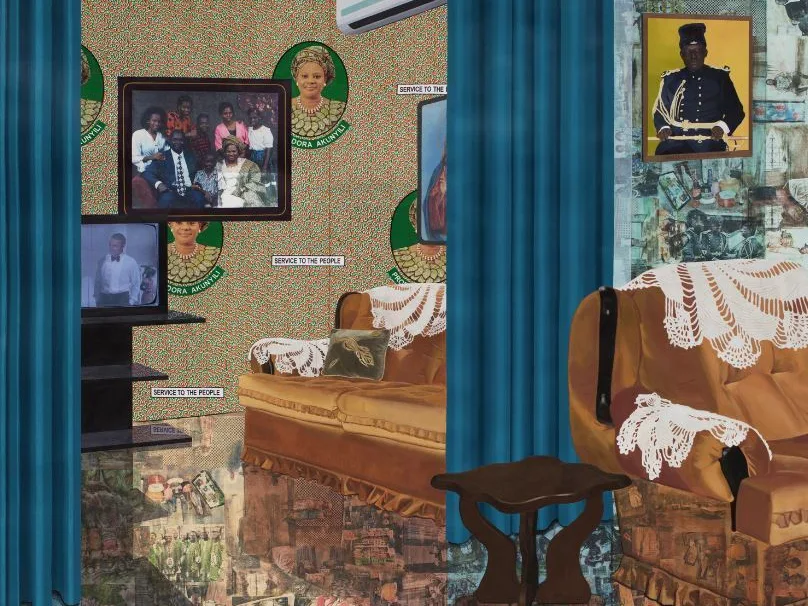

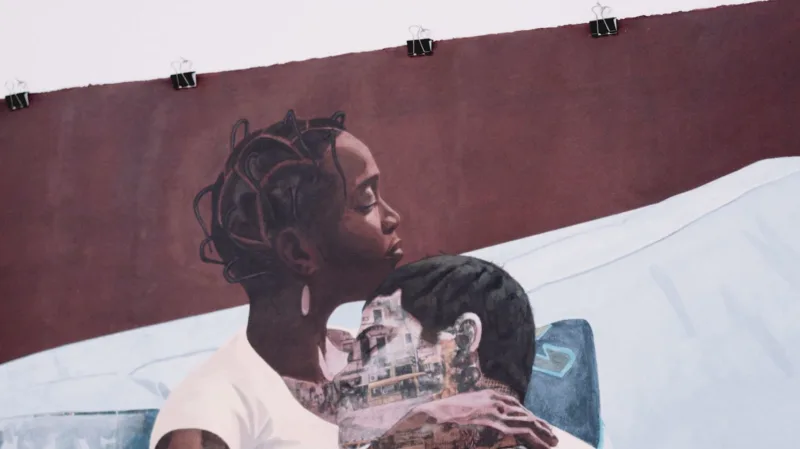

With Njideka Akunyili Crosby, the artist’s own globally entangled biography, her lived reality oscillating between two continents and cultural circles offers a point of departure. The loving relationship – inevitably politically charged – between the artist, a black woman who grew up in a small city in Nigeria, and her husband, a white American, finds its way into her work, as does her migration experience and her strong and lasting attachments to her Nigerian homeland. Reflections on her own identity with regard to the collisions between diverse familial, political, and (pop)cultural influences and traditions, as well as the resulting conflicts and hybrids, are directly mirrored in her precisely composed spatial arrangements, which incorporate both architecture and design. The intimate scenes and familial memories that are incorporated into Akunyili Crosby’s spaces, not unlike Henrike Naumann’s interior installation spaces, provide access to personal experiences, at the same time narrating stories that go far beyond private life. Having grown up in Zwickau in the former East German Democratic Republic in the years immediately following German reunification, Henrike Naumann negotiates the burgeoning of new right-wing movements in her work. The complexity of the German-German history as manifested in the aftereffects of the reunification of East and West Germany, which connect directly with questions of belonging and identity, and with perceived insecurity about both, become her themes. Her installation which fills the space, conceived especially for the Haus der Kunst and integrating original furniture from the building’s National Socialist past, strikingly highlights the way in which far-reaching economic and societal upheavals, political ideologies, and power structures are manifested in design, decor, and interior furnishings, and hence in the intimate sphere of the individual. The tension between private and public/political spaces, between the interior and exterior is concentrated in the works of Adriana Varejão through the representation of saunas and baths but also in the activation of Brazil’s colonial past, the violence exercised by Europeans on individuals, as well as on entire populations, in the course of imperialism and the slave trade, leaving behind a wound that has yet to heal. Her multilayered, anthropologically informed works mirror processes of transnational exchange, calling attention (with reference to the exoticizing cannibalism fantasies cultivated by the West) to forms of incorporation and transformation of the highly diverse cultural influences upon which modern Brazil is based. Pursuing her interest in the genesis of modernist forms of expression, Leonor Antunes tracks the global, cross-border transfer of people and things and the resulting hybridization of forms and ideas, establishing imaginative relationships to and between the works and biographies of artists, architects, and designers whose lives have themselves been shaped by migration and by multifarious cultural and aesthetic influences. In a symbolic way, the series of sculptures she presents at the Haus der Kunst, so reminiscent of the permeable forms of tropical as well as South American, Asian, and African architecture, gets to the heart of the impossibility of locating clear contours between interior and exterior, thereby offering a representative answer to the questions posed by the exhibition, which revolve around identity, while at the same time directly taking up the social and political concerns of our time.

Anna Schneider is curator at Haus der Kunst and curated the exhibition "Interiorities". This article is an excerpt from her essay for the exhibition catalogue, that will be published in April.