Shortened version. The full interview can be found in the exhibition catalog.

Carina Bukuts: For many years, you were director of Galerie Lelong in Zurich (formerly Galerie Maeght), where you exhibited women artists such as Heidi Bucher and Louise Bourgeois. When did you start working at the gallery?

Elisabeth Kübler: In 1969, my first husband, Jörn Kübler, and I went to Paris to familiarise ourselves with the gallery and its history, and the gallery in Zurich was already opened by the autumn of 1970.

CB: What distinguished the gallery and its programme?

EK: I don’t know if you’re acquainted with the gallery in Paris, but Aimé Maeght founded Galerie Maeght there in 1946 and exhibited artists such as Henri Matisse, Pierre Bonnard and Wassily Kandinsky. It was probably one of the most famous galleries in Paris at the time. In 1964, he also set up the Fondation Maeght in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, near Nice. Early on, he had wonderfully innovative ideas, such as rotating between different gallery locations. Today, other galleries do this as well, of course, but I think he was one of the very first to do so.

CB: What happened after you came back from Paris and settled in Zurich?

EK: From 1970 until his death in December 1975, Jörn Kübler was director of the gallery. I was initially responsible for the huge prints department, which had etchings, lithographs and albums by Braque, Miró, Matisse, Giacometti, Chillida, Tàpies and many others. I was also always doing a lot of travelling for the gallery to meet artists. When Jörn was travelling – and later during his illness – I took over his duties. The transition of my areas of responsibility within the gallery was thus pretty seamless. I remained director of the gallery until 1994.

CB: What was the gallery landscape like in Zurich back then?

EK: Everything started at the same time. There was already the gallery of Renée Ziegler, the niece of the famous Bernese collector Hermann Rupf. She founded her gallery in 1959, which was actually the first gallery for contemporary art in Zurich. Of course, Annemarie Verna’s gallery was very important, too, as was Bruno Bischofberger’s gallery.

CB: So it was a time of new beginnings, with many new protagonists.

EK: Yes, exactly. Zurich suddenly became so interesting. Both for the financial sector and for the arts.

CB: That actually continued seamlessly into the 1980s, didn’t it?

EK: Yes! In the 1980s, the cultural awakening in Zurich was even more noticeable than before. Many factories were shut down back then. Not only the Rote Fabrik and the art magazine “Parkett” emerged out of this, but also the Löwenbräu site with the Kunsthalle Zürich and the Migros Museum für Gegenwartskunst in the 1990s.

CB: That sounds like an exciting time for a comparatively small city like Zurich. In nearby Basel, Heidi Bucher had an exhibition at Marie-Suzanne Feigel’s Galerie d’art moderne in 1956. Is that where you discovered her works?

EK: Unfortunately, I didn’t see that exhibition. It was only after we had already taken over the gallery that we came across Heidi’s works. We were actually a very international gallery and represented numerous artists exclusively, including Joan Miró, Marc Chagall, Georges Braque and Alexander Calder. I had nothing to do with Swiss art at that time. Heidi was the first Swiss artist I dealt with professionally. I exhibited the American artist Ed Kienholz, and he then introduced us to each other and recommended that I exhibit Heidi. Then I went to her studio, looked at her work and was very impressed by it. That was the early 1970s.

CB: How did Ed Kienholz know about Heidi Bucher’s works?

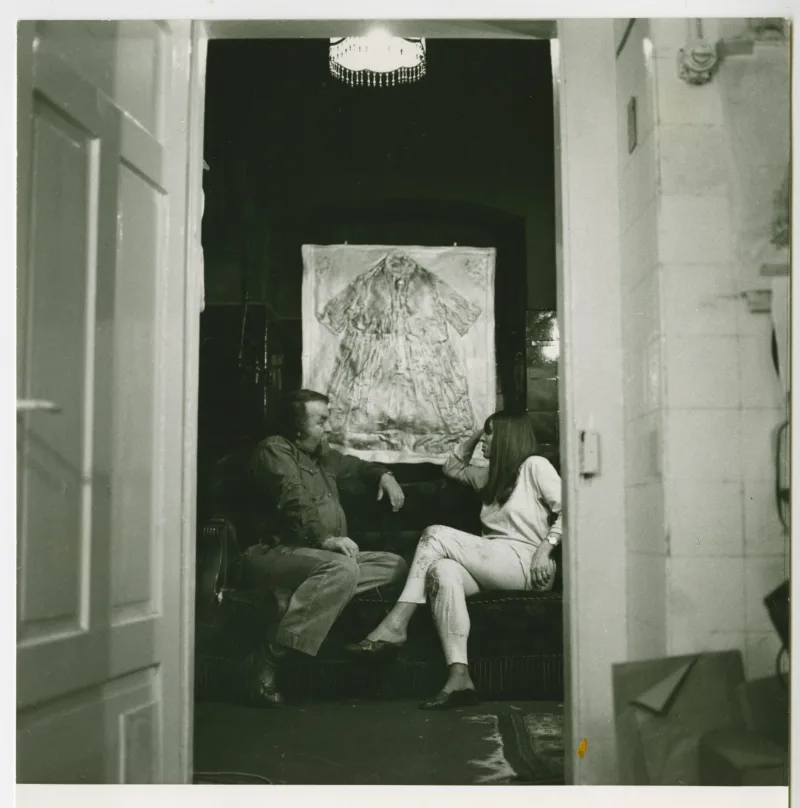

EK: The two were friends and knew each other from Los Angeles, where Heidi had lived with her husband and children in 1972/73 (fig. 1).

CB: At the beginning of her career, Heidi Bucher did not start making art right away, but worked instead with textiles. In those days, she was studying at the Zurich School of Arts and Crafts under Johannes Itten. Did you ever talk to her about the early years of her art and her studies?

EK: No, that was never a topic of discussion between us. She always let the past be the past. She was so completely interwoven with her art and so truly engaged in her new works, there was no room for the past. We had a lot to tell each other. She would spend the night here and we even celebrated Christmas together, but she never wanted to talk about the past. She was very focused on the present.

CB: When did you first exhibit Heidi Bucher’s work at Galerie Maeght?

EK: The gallery had many rooms, and for a while, I even organised three exhibitions simultaneously so that I could also exhibit the women – including other women artists such as Anna Oppermann. The large gallery room was often occupied by our main artists, with whom we had exclusive contracts. But Heidi had three large exhibitions with us: the first time in 1977, then in 1979 and 1981 (fig. 2).

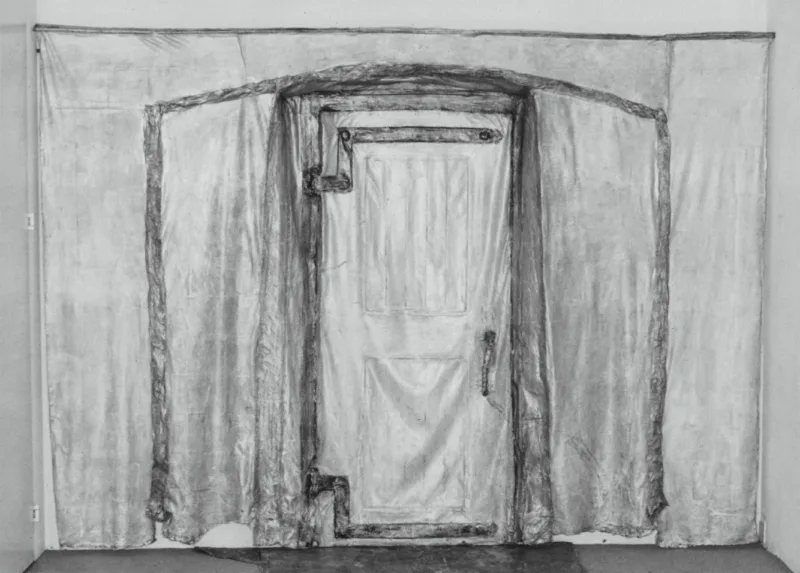

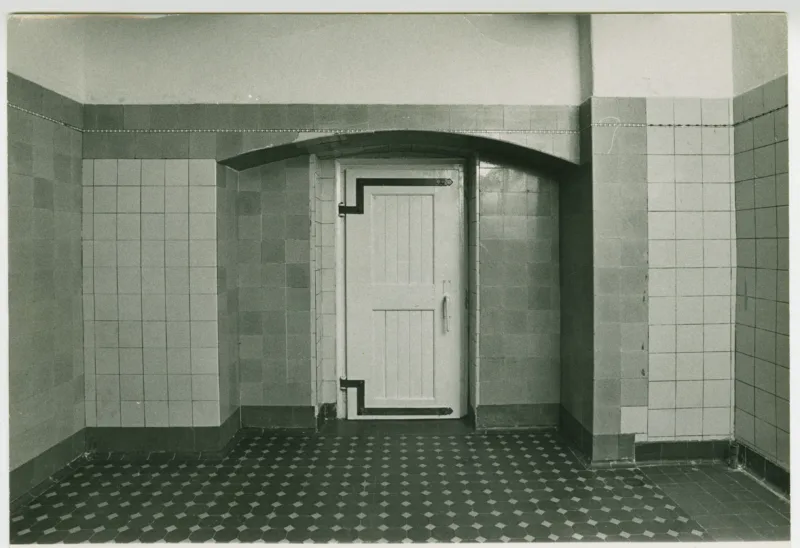

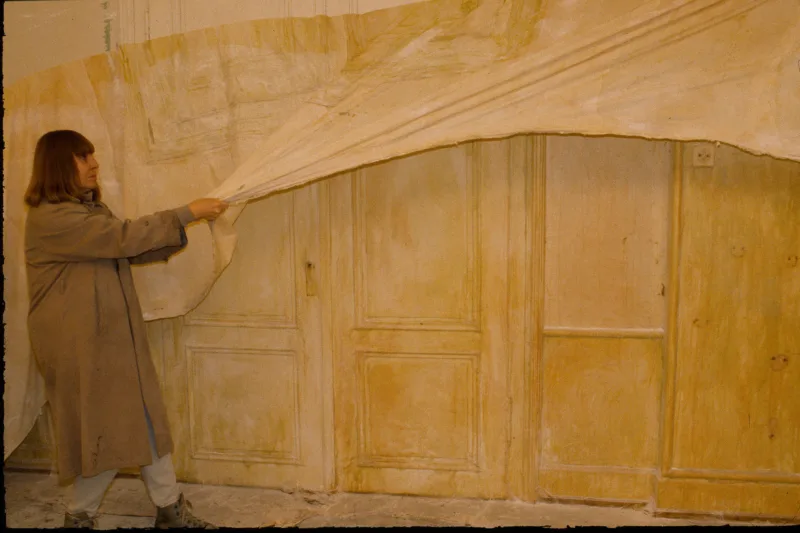

CB: In 1977, in the first of those exhibitions, titled “Einbalsamierungen” (Embalmings), she showed one of her earliest three-dimensional latex works. For “Borg” (1976; fig. 3), she had applied latex and mother-of-pearl onto the walls of her studio – in the cold-storage room of a former butcher’s shop – and when the material had dried, had peeled it off and used bamboo poles to install it as a room in the gallery (figs. 4 and 5). It was a very unusual technique and aesthetic. How did the Zurich public respond to it?

EK: Heidi was very well connected in Zurich, and collectors also purchased works from the exhibition, precisely because they already knew her. Otherwise, it was incredibly difficult to approach international collectors. It was simply too early. And not only that: she was a woman. We all know what a stigma that was back then – even for someone like Louise Bourgeois. We showed her at the gallery in Paris at the time, and my colleagues, who were all men, were not as enthusiastic about it as I was. I had seen Bourgeois’s work at the MoMA in New York in 1982, and I was quite happy that I was then allowed to do a show with her (fig. 6). With the catalogues of the American exhibition, I went from one museum to another in Germany to ask if they might want to exhibit Bourgeois as well, but no one wanted her. What made it difficult to convince museum directors and collectors of her work was not only the fact that she was a woman, but also because her works were so theatrical. And it was much the same with Heidi. One has only to think of all those dresses and the underwear she covered in latex and exhibited.

CB: Her works were not only feminine, but – similar to Bourgeois – there was also something very uncanny about them.

EK: Definitely. Just think of that cold-storage room in the butcher’s shop. It was an enclosed, square space that was quite scary and smelled very strongly of latex. It was really quite eerie, but – in my opinion – that also gave the works their depth, background and tension. Simply exhibiting clothes would not be worth mentioning, but the latex gave them both this morbid quality and a sense of transformation into something else, into a new life.

CB: Yes, it was probably a very different experience for a collector or gallery owner to visit Heidi Bucher’s studio. They were confronted there with a completely different reality of artistic production.

EK: Yes, absolutely, and how! But, of course, it was precisely this morbid quality that was so fascinating, because it was so different and autonomous. I think that’s also what the male world probably still has difficulties with. To accept this otherness and this decidedly feminine aspect of art.

CB: You mentioned earlier that the few collectors who purchased Heidi’s works did so mainly because they already knew her. At that time – the late 1970s and early 80s – did she already have connections to curators in Swiss institutions? Were they interested in showing or acquiring her works?

EK: No, although she did have a smaller exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Winterthur in 1983. She was actually supposed to have a more comprehensive exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Thurgau in the early 1990s, which she very much looked forward to. Elisabeth Grossmann was curator there at the time and wanted to realise the exhibition together with her. She then also did a project together with Heidi in Kreuzlingen, on Lake Constance, in 1988.

CB: At the Bellevue sanatorium?

EK: Yes, the two of them climbed over a fence and had a look round.

CB: It was the clinic of the Swiss psychoanalyst Ludwig Binswanger, where personalities from the world of culture, such as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Aby Warburg, were occasionally patients. A place that is just so charged with meaning. For her work “Das Audienzzimmer des Doktor Binswanger (Sanatorium Bellevue, Kreuzlingen)” [The Consulting Room of Doctor Binswanger (Bellevue Sanatorium, Kreuzlingen); figs. 7 and 8], she took the analyst’s consulting room, covered it with latex and later presented it as a floating installation (figs. 9 and 10).

EK: Yes, exactly. She wanted to exhibit these works, but tragically, Heidi died before she had the chance to do so. After that, Elisabeth Grossmann no longer felt like going ahead with it, which was a great pity. Heidi knew about the importance of her own work, and she was convinced that it would one day be recognised. But she also knew that she would not live to see it – and that was, of course, a tragedy for her.

CB: When Bucher was in the USA, you two didn’t know each other yet. Nevertheless, I would like to return briefly to this episode in her life to talk about the wearable sculptures “Bodyshells”. There’s one video in which you can see her, her children and her husband at the time, Carl Bucher, performing in the costumes on Venice Beach, in Los Angeles (figs. 11 and 12). What becomes visible here is the performative character of Bucher’s works.

EK: Yes, exactly, and that also comes into play when you look at the “skinnings”.

CB: There’s also some video footage of her applying latex to walls and then peeling it off. Everything is very well documented, and it seems that she was interested not only in presenting her works as sculptures or installations in exhibition spaces, but also in recording how they were produced. For the videos, her sons, Mayo and Indigo, often conducted short interviews with her and stood behind the camera.

EK: This shows once again that Heidi knew that her work mattered and was worth documenting.

CB: Looking at how she transformed or dealt with space, comparisons are often made to contemporaries. It shows that there was an exciting focus on space during this period, that artists were dealing with it not only as architecture, but above all with its multi-layered levels of meaning.

EK: Yes, the best examples of this are the Bellevue sanatorium in Kreuzlingen and the Grand Hôtel Brissago in Ticino in 1984 (figs. 13 and 14). The sanatorium was, as you’ve already mentioned, a very important clinic.

CB: Heidi Bucher very specifically chose spaces whose history she – literally – stripped away and exhibited. The space as a shell.

EK: Yes! With her, the history of the space is always taken along into the exhibition space. The rooms are fully charged with meaning, and so are her casts of them. They may appear to be empty, but they are certainly not. That’s what’s so special about history, that it leaves its traces everywhere. Houses have a life, spaces have a life – and Heidi was very absorbed by this idea.

CB: Since Louise Bourgeois’s name has already been mentioned several times, I would like to talk about a material that was used by her and Heidi Bucher and even by Eva Hesse: namely latex. When we think about latex as a material today, one factor that immediately comes to mind is conservation (Fig. 15). Did that prevent collectors from buying works, and was that perhaps another reason museums didn’t want to collect Heidi’s works?

EK: Yes, I think this definitely played a role and prevented people from buying. And I also have to admit that the work by Heidi in my own collection is kept in a glass case, so that it’s perfectly protected. This works for my piece; but when the latex hangs freely in an open space, it’s much more difficult.

CB: I don’t know if you can answer this question, but to what extent did Heidi herself also take the durability of her works into consideration?

EK: If she did give any thought at all to the future, I think it would have been about the major projects. We hung the “Herrenzimmer” [Gentlemen’s Study; 1978/82; figs. 16 and 17] in the gallery once. Maybe she was already thinking about how to preserve it, because it was already relatively complex. But on the whole, I don’t think that any artist is worried about the shelf life of his or her works. That would be more like calculation and production. It’s about much more than that. It’s about urgency. Without urgency, there would be no art at all. At least not for me.

CB: Heidi Bucher began to create an archive of her works relatively early on, which also shows that she reflected on the future.

EK: To be honest, I didn’t know anything about the archive. But then it makes sense somehow. She had a fantastic ability to assert herself. She was as tough as nails when it came to selling herself. She was great at that – but the time simply wasn’t right yet. That was the unfortunate part. She could be very self-confident, but men didn’t like to see women behaving like that in those days.

CB: It’s great that she had such self-assurance, despite the fact that she had no particular commercial or institutional success. She didn’t let that stop her from working on her art.

EK: Absolutely. She never had any doubts about her own art and that’s probably why she created the archive.

CB: The 1970s were marked by the discourse on feminism. In 1975, there was an exhibition at the Städtische Kunstkammer in Zurich, for which Heidi Bucher was a kind of inspiration. The title was “Women See Women”. Interestingly, Heidi didn’t show anything there herself. What was Heidi’s relationship to the women’s movement in Switzerland? After all, Swiss women didn’t get the right to vote until 1971.

EK: Yes. It was, of course, an issue at the time, but it was never really present in my personal conversations with Heidi. The same was true for artists, such as Meret Oppenheim, with whom Heidi was also very good friends, or Louise Bourgeois, with whom I was in close contact – none of them wanted to know that much about it. They would say: “I’m an artist. and that’s it!” They wanted to be perceived as artists and in no way marginalised as feminists just because they were women.

CB: Posthumously, of course, many of these artists are credited with an important role in the feminist discourse.

EK: Yes, but people didn’t know that at the time. You have to remember that it all began in 1970. There were women who did talk about it, but they weren’t specifically artists.

CB: Yes, they wanted to make their contribution through their work. Just as you presumably also wanted to do as a gallery director, right?

EK: Yes, it was very important to me to work with women artists – as best as I could, to the best of my ability. But, of course, I couldn’t show only women artists either.

CB: But was this attitude that you had – consciously showing women artists – unusual at the time, or were there other galleries in Zurich that were borne by a similar consciousness?

EK: No, not that I can remember. Elisabeth Kaufmann also exhibited women artists in Zurich, but she came after us.

CB: Was it generally similar for the institutions in Zurich or in Switzerland?

EK: Yes, there was no interest in exhibiting women there, and the same goes for Germany. I knocked on many doors all over the place there with the books under my arms and approached various museums, but they found all of it appalling.

CB: Fortunately, that’s no longer the case.

EK: Yes! It’s really quite astonishing when you consider that Bourgeois had already made a name for herself in America by that time and yet was met with total rejection in this country.

CB: Were there any artists around Heidi Bucher with whom she exchanged ideas and who perhaps helped to shape her thinking?

EK: Towards the end of her life, she became friends with Maria Lassnig and had many things in common with her. Lassnig was a unique painter whose works were at times also evil or sinister. Heidi also thought that what Anna Oppermann did was great. The labyrinths she built and her drawings were fantastic. It’s actually significant that Heidi was friends with her, because Anna’s work was also very, very feminine. Almost disturbingly feminine. Maybe not for us as women, but for men, because her works were extremely trenchant.

CB: In Lassnig’s paintings, there’s always a preoccupation with the female body, and she, too, had a certain fascination for the eerie.

EK: Yes. Her works are not only very aesthetic, but you can also discover a great deal in them that’s very sinister.

CB: Definitely! That’s what I also find so interesting about Heidi Bucher, namely that there’s a subtleness which, to some extent, also has psychoanalytical aspects. The way memory and history are interwoven in her work. The very idea of that cold-storage room where she made “Borg”, her first latex work, sends shivers down your spine. With the “Herrenzimmer” [Gentlemen’s Study], there was also a personal level, because it was her family’s former home in Winterthur. What kind of relationship did she have with her family?

EK: Her family’s old house had a strong presence, of course, but she never talked about her mother or her father.

CB: The decisive role her sons had is demonstrated not only by the fact that they repeatedly accompanied their mother’s work, but that they have also administered her estate for decades and have made a great effort to make Heidi Bucher’s work accessible to a wider public.

EK: Yes! Her sons were the people she trusted most. But her friends, such as Ed Kienholz, were also great supporters of her work. She had a very good relationship with him and his wife, Nancy. Once, they came to the gallery feeling very excited and asked if I would agree to show their work as being by Ed and Nancy Kienholz instead of simply Ed Kienholz. It was a big decision for them. Of course, I said I didn’t mind at all, and from the next exhibition on, we presented them that way. But many people then started talking about it.

CB: What did people say at the time?

EK: That it was unnecessary. But it made a lot of sense to me that they renamed themselves, because Nancy always collaborated on the works.

CB: That’s a nice example of how work by women was beginning to be appreciated in this form, too, in that works were no longer simply signed with the man’s name, so that Nancy Kienholz, for example, also became part of art history.

EK: There were really very few women in art at that time – or to be precise, there were, of course, some, but they had no visibility at all, which was a great, great pity.

CB: Fortunately, that’s changing right now. More and more galleries have women artists in their programmes, and museums, too, would get into trouble if they exhibited and collected only works by men – but this development has taken long enough.

EK: The tragedy, however, is that it has taken so long, because it simply wasn’t an issue at the time. Unfortunately, the fact that it was predominantly men who were exhibited seemed unalterable and there was no way to fight back.

CB: It’s great that you believed in women artists such as Heidi Bucher, Louise Bourgeois and Anna Oppermann – despite all the obstacles. With the publication on Bucher’s first exhibition at the gallery, you created an important contemporary document during the artist’s own lifetime. I think this is still of immense value for subsequent generations.

EK: Yes, I thought it was important, and the exhibition at the Haus der Kunst proves me right in a certain way. It’s terrific that this is being done and really a great pity that Heidi didn’t live to see it herself.

Elisabeth Kübler was director of Galerie Maeght (later Galerie Lelong) in Zurich from 1970 to 1994. Until a few years ago, she was vice-president of the gallery’s board of directors