The artists’ index of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst (House of German Art) is one of the central and most noteworthy sources in the collection of our Historical Archive. Sabine Brantl discusses this document in her blog post, which can also be viewed digitally in the Archive Gallery.

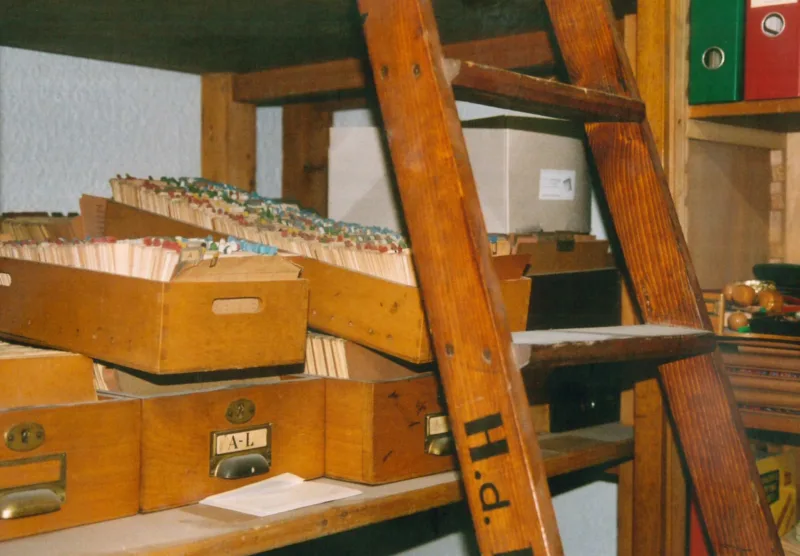

The index was discovered during making Haus der Kunst’s archival holdings available for research. Since the post-war period, these and other documents and objects had previously been stored in the museum basement, in a “vegetable cleaning room” set up for the restaurant in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst. In 2004, I examined this holding and made it accessible for scholarly research. When we opened the Historical Archive to the public the following year, Haus der Kunst was one of the few art institutions at that time that was critically examining its role under the Nazis. Although the architecture of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst and the function of art under National Socialism had already been thematized and studied, the exhibition business itself and how it functioned both organizationally and economically behind the façade of art, power, and propaganda had previously been largely ignored. Documents found during the development of the Historical Archive are important sources for learning more about these matters.

In all, 2,486 artists exhibited works – in some cases several times – between 1937 and 1944/45 in the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” (Great German Art Exhibition) held in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst. The annual shows were considered the most important exhibitions for the presentation and sale of “German” art (see my blog post from April 6, 2020). The prerequisite for applying to participate was membership in the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, which, since November 1933, had been compulsory for professional artists; this was more or less a coercive measure.

In this context it should be mentioned that documents relating to the first “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” are not in the archives of Haus der Kunst or other institutions. It was not until 1938 that the systematic creation and management of documents began.

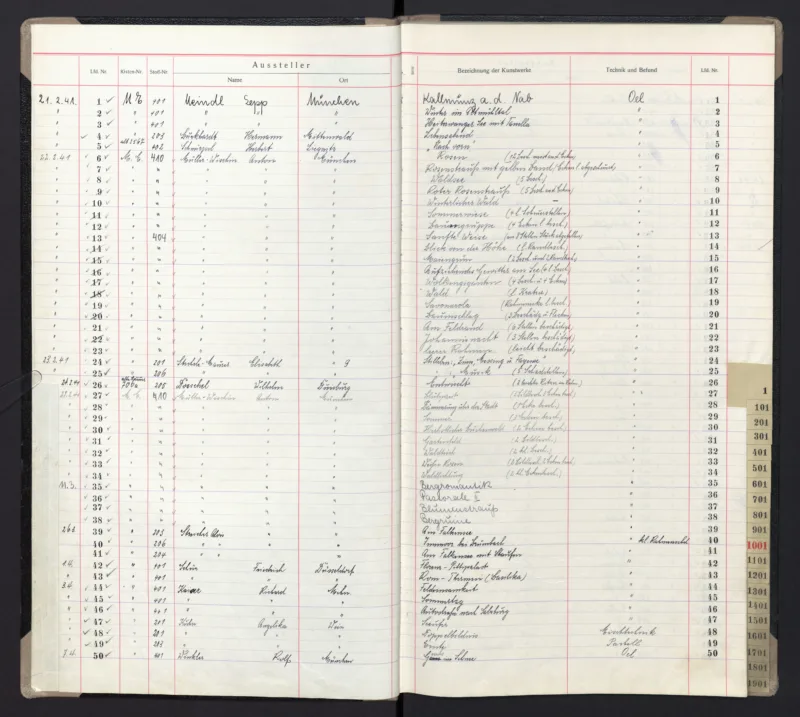

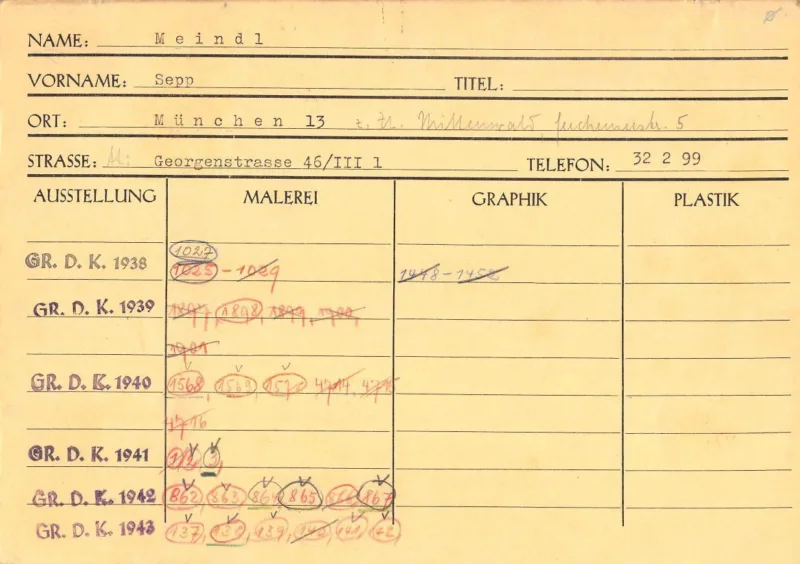

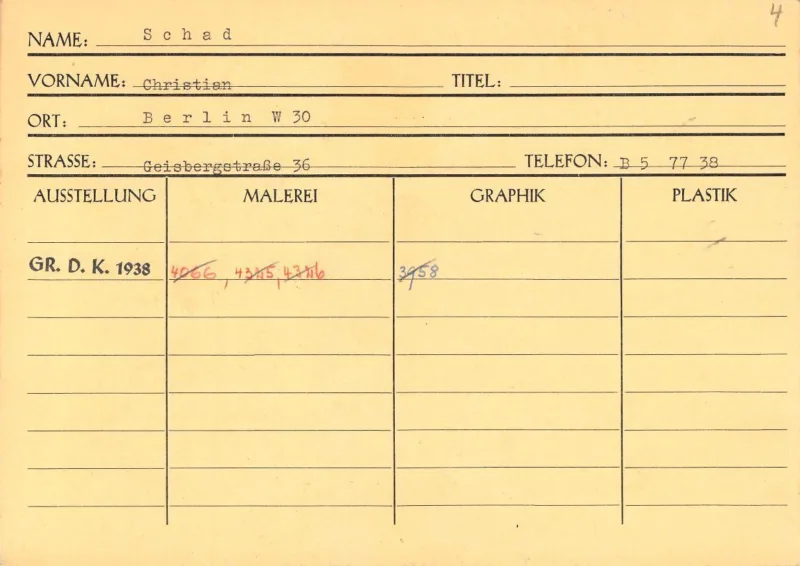

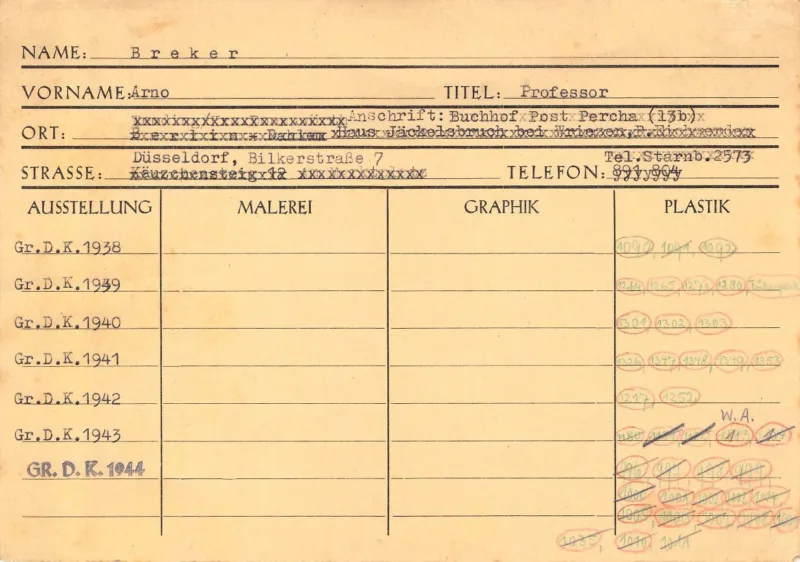

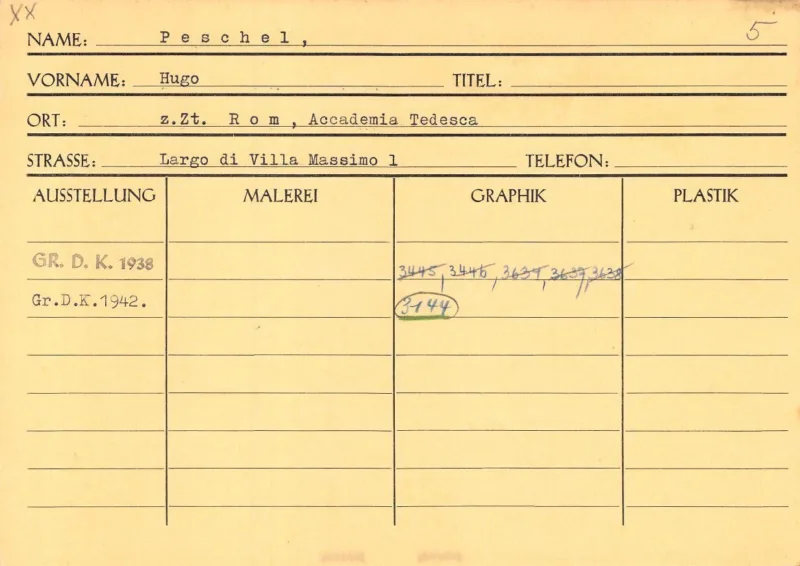

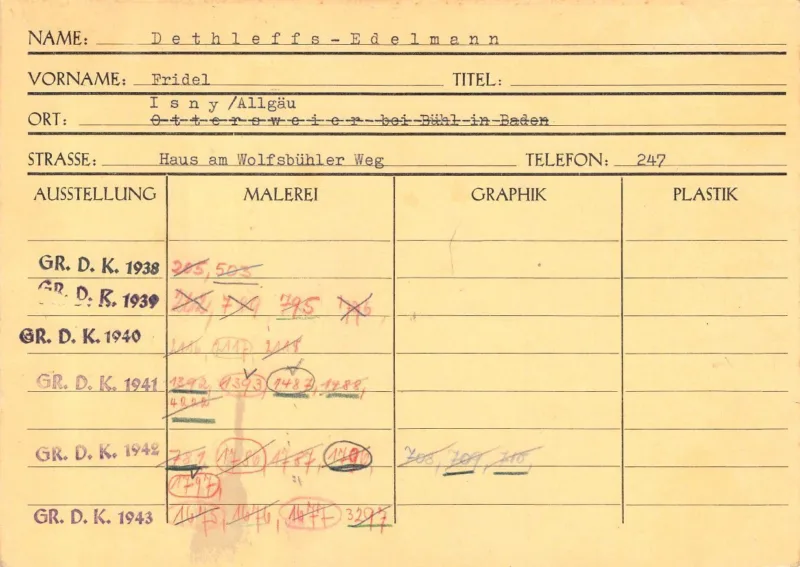

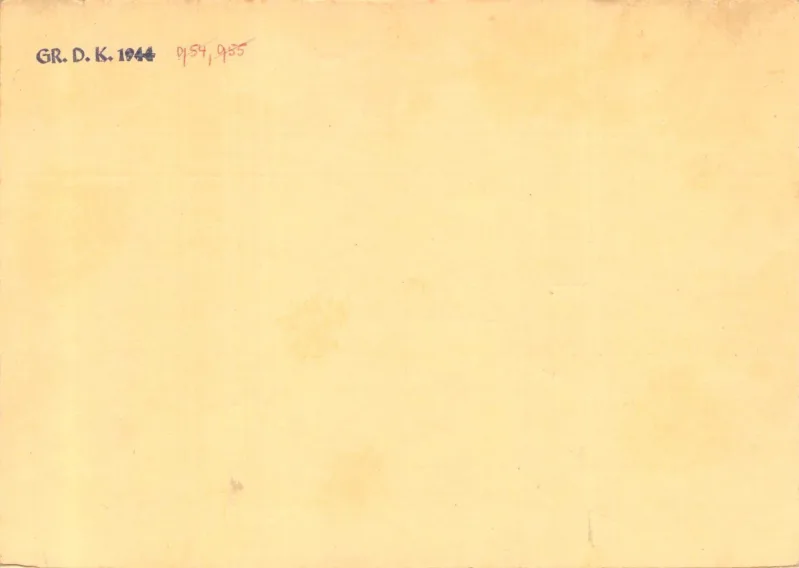

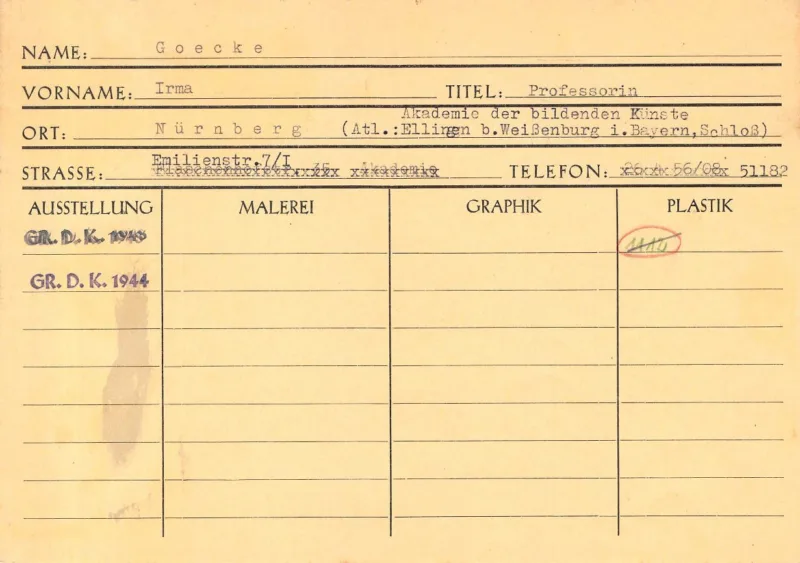

What insights does the artists’ index provide, and how is this resource used for research? The artists’ index is a collection of preprinted 15 x 21 cm index cards. When an artist first requested application forms, an index card was created and the applicant’s address and the year of the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” were typed or stamped on it. If the artist failed to enter a work, the index card remained without further entries. All submitted works were first recorded in the order of their arrival and listed according to the categories “painting,” “graphics,” and “sculpture” in posting ledgers. A sticker was placed on the back of the submitted painting or graphic, and the work’s serial and submission number were noted on it. Sculptures were labeled. Unfortunately, these ledgers were only preserved from 1941 onwards. The submission numbers, however, were also entered in the artists’ index.

Many of the inquiries submitted to our Historical Archive concern paintings and graphic works, on the back of which remains a sticker from one of the eight “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung.” The high number of inquiries—generally made by private individuals—allows us to assume that artworks surrounding these exhibitions also appeared on the art market after 1945, especially when the works depicted “harmless” subjects, such as landscapes, still lifes, portraits, and rural scenes and had not been accepted for presentation. In the case of an unsigned work, the name of the artist can be determined using the submission number. Additional information also can be found, for example, in notes about a work’s acceptance, rejection, or sale, which was recorded on the artists’ index card by hand in symbol form. A submission number with a line through it meant that the work had been rejected; a circle signified an exhibited work; a check that the work had been sold. If the submission number was underlined, the work had been shortlisted as a replacement for an exhibit that found a buyer in the first few months of the show.

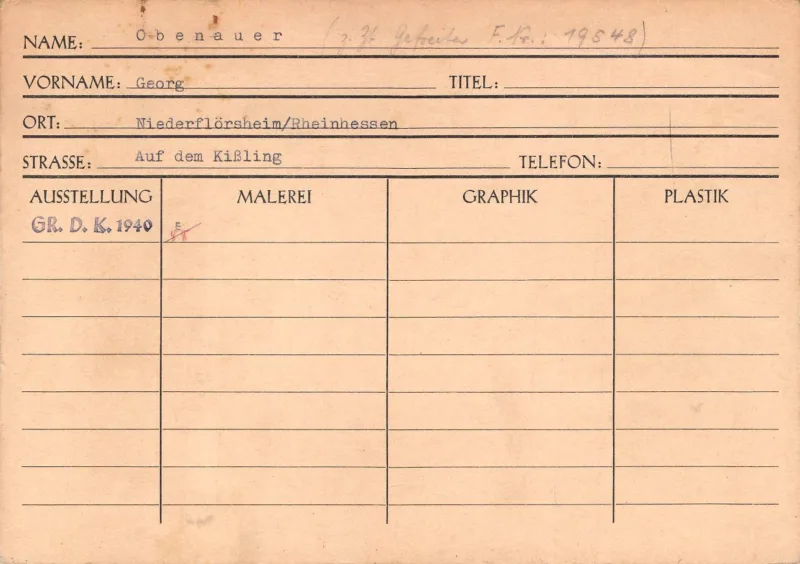

Apparently, it was assumed that works would be submitted that did not conform to the National Socialist conception of art and, thus, were subsequently labeled “entartet” (degenerate). The capital letter “E” above a submission number classified the work accordingly. If you research the artists’ index for this notation, you will find just a few entries. Such a notation was made on, for example, the index card of the now largely unknown painter Georg Obenauer, who studied at the Munich Art Academy in the late 1920s; five graphic works submitted in 1943 by the painter and sculptor Alois Wünsche-Mitterecker were also marked with an “E.” A note “SS-Div [ision] Wiking” written in pencil indicates that Wünsche-Mitterecker was a member of this division of the Waffen-SS established in 1940 and had served as a war painter.

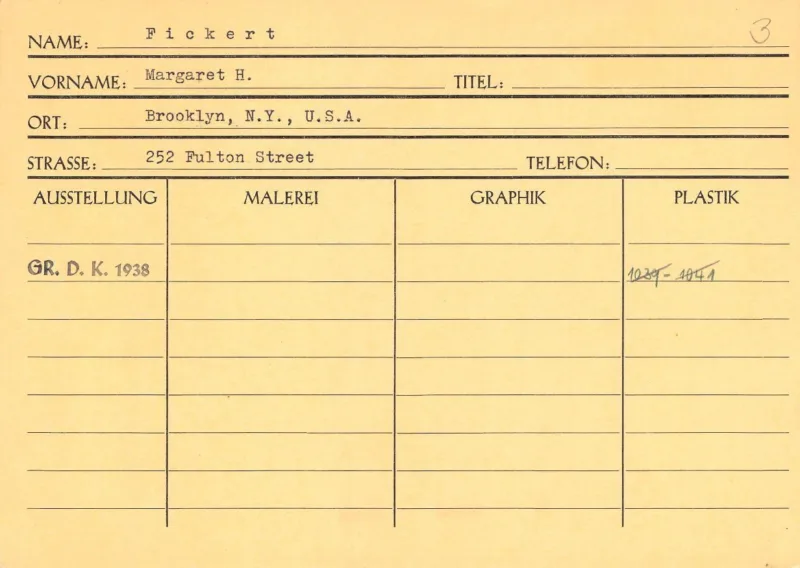

According to the exhibition regulations, only artists born in Germany could participate in the exhibitions. Following the “Anschluss” (annexation) of Austria in 1938 and the cession of the Sudeten area by Czechoslovakia to the German Reich, this admission criterion was expanded. Artists who lived abroad could also submit works to the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung.” However, such participation was extremely low, and only a few international applications were submitted, for example from Italy, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, and the US.

The proportion of female artists who applied to the shows was also relatively low and constituted just 15 percent of the names listed in the artists’ index. The proportion of women who exhibited works in the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” was even lower, only 9.3 percent. These numbers are hardly surprising, considering how the artistic contribution of women was perceived in the art world until well into the mid-twentieth century, and that academic training and professional participation were only possible to a limited extent. In addition, the National Socialist art policy provided no room for female visual artists. The 1,361 women in the artists’ index include the first women to have studied at German art academies. The portrait, flower, and landscape painter Fridel Dethleffs-Edelmann, for example, began studying at the Badische Kunstschule (now the State Academy of Fine Arts) in Karlsruhe in 1919. The textile artist Irma Goecke was the first female student to be accepted at the Düsseldorf Art Academy. From 1941 to 1966 she was artistic director of the Nuremberg tapestry manufactory, which also made tapestries for the Nazi party’s rally buildings and SS accommodations. Goecke submitted a work only once, in 1943, to the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung.”

The Haus der Deutschen Kunst’s artists’ index comprises a total of 9,073 applicants, around 30 percent of whom exhibited in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst. Thus, the artists’ index provides a more extensive picture of the art scene during the Nazi era than, for example, the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” catalogues do. Against this backdrop, the fundamental question arises as to which artists – apart from the already familiar names in this context – applied to the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung,” thereby hoping to participate in the most important exhibition of Nazi art policy. It is not uncommon for biographical constructs of rejection and resistance, defamation and withdrawal, and a ban on professions and exhibitions to be shaken or disturbed. With this in mind, the Haus der Deutschen Kunst’s artists’ index is an important resource for research on art and the art market under National Socialism.

Sabine Brantl is head of the History Department at Haus der Kunst. As curator, she is responsible for the exhibitions of the Archiv Galerie. In 2004 she development a concept for the establishment of Haus der Kunst’s Historical Archive.