It is only in recent years that research has increasingly focused on the “Große Deusche Kunstausstellung” [Great German Art Exhibitions] the most important shows for the presentation and sale of art under National Socialism. In her blog article, Sabine Brantl informs about these exhibitions, with which the Haus der Deutschen Kunst [House of German Art] became the central venue of National Socialist art policy.

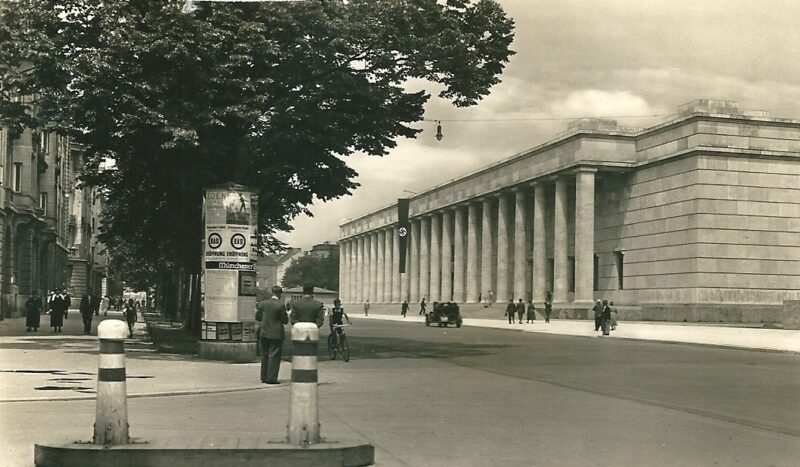

The Haus der Deutschen Kunst opened on July 18, 1937 with the presentation of the first “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung”; it was a spectacular and lavishly staged media event and was reported in national and international newspapers. Quoted in great detail, Hitler’s opening speech included his declaration of an “unrelenting cleansing war” on the intensely hated modernism and that the standard of all artistic achievement lay in the “Aryan” race. This was a blatant expression of the fact that Nazi art policy also was essentially based on racial politics and constructs of exclusion and affiliation and was not simply a power apparatus for eliminating an undesirable modernism. The “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen” established an aesthetic and political space that served to implement and display these ideological goals until the end of the Second World War.

From an organizational perspective, the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen” were sales exhibitions like those that had been staged since the 19th century. In contrast to the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen,” these commercial shows were regional and autonomous and typically organized by local artist organizations or art associations. A prerequisite for participation in the exhibitions at the Haus der Deutschen Kunst was membership in the Reich Chamber of Fine Arts, which had been mandatory for the artistic profession since November 1933. Over 9,000 painters, sculptors and graphic artists submitted works - some more than once – in the total of eight shows. Even artists such as as the painter Gabriele Münter, a founding member of the “Blaue Reiter” group, which had helped define the avant-garde before the First World War, decided to submit works to the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung.” In late May 1937 she wrote to her partner Johannes Eichner, “I would risk submitting ‘Vereiste Straße;’ it has impressed many lay people ... I also would dare to submit ‘Jochberg.’ That is German, a German landscape.” Four weeks later, however, Münter informed Eichner that “the selections had been negatively received” (quoted from: Gisela Kleine’s Gabriele Münter and Wassily Kandinsky - Biography of a Couple. Munich: 1993, pp. 627 and 775). Münter did not apply to the show again.

Initially, a jury of artists selected which works would be presented in the exhibition. In June 1937, however, Adolf Hitler, who had been extremely dissatisfied with the exhibits originally planned for the first “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung,” made his personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, the director of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst Karl Kolb, and Gerdy Troost, the widow of the building’s architect, responsible for the selection of the submitted works. Hitler’s opinion, nevertheless, remained decisive.

In 1940, for example, the exhibition management was asked to scrutinize the submitted sculptures even more rigorously. In addition, a few days before the opening of the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung,” works by at least 29 artists - including paintings by the otherwise highly esteemed painters Karl Theodor Protzen and Heinrich Zügel - had to be removed because Hitler deemed them to be “modern.”

![Typescript “Erfahrungen in Bezug auf das Hängen und Stellen der Arbeiten in der Großen Deutschen Kunstausstellung 1940“ [Experiences with Regard to Hanging and Placing the Works in the Great German Art Exhibition], July 23, 1940 © Haus der Kunst, Historisches Archiv, HdDK 35](https://www.hausderkunst.de/uploads/fragments/images/Import/_artPracticeFullWidthImage/GDK_3a_2023-06-20-153843_xicm.jpg)

![Typescript “Erfahrungen in Bezug auf das Hängen und Stellen der Arbeiten in der Großen Deutschen Kunstausstellung 1940“ [Experiences with Regard to Hanging and Placing the Works in the Great German Art Exhibition], July 23, 1940 © Haus der Kunst, Historisches Archiv, HdDK 35](https://www.hausderkunst.de/uploads/fragments/images/Import/_artPracticeFullWidthImage/GDK_3b_2023-06-20-153843_zvwa.jpg)

The “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen” promoted an aesthetic architype that rendered art a “national” matter. Although the shows in the Haus der Deutschen Kunst only presented a limited number of openly propagandistic works, they conveyed a kind of walk-in world view of the National Socialist regime in the 6,000 square meter exhibition space; this included the concept of a national home, the relationship between the sexes and the role of the family, workers, farmers and soldiers. It constituted a superficial “ideal world” that was intended to visually captivate the “Volksgenossen” and simultaneously demonstrate a commitment to the Nazi state and its ideals of the strength, beauty and purity of the “Aryan” race. Printed matter, such as exhibition catalogues, art magazines and postcards as well as reports in German newsreels, also ensured that the works on display were popularized and inscribed in the visual memory of an entire generation.

![“Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” 1940. Hall of Sculpture in the east wing of the building. In the background: Adolf Wamper’s “Genius des Sieges” [Genius of Victory] © Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Photothek](https://www.hausderkunst.de/uploads/fragments/images/Import/_artPracticeFullWidthImage/GDK_4_2023-06-20-153843_qlbe.jpg)

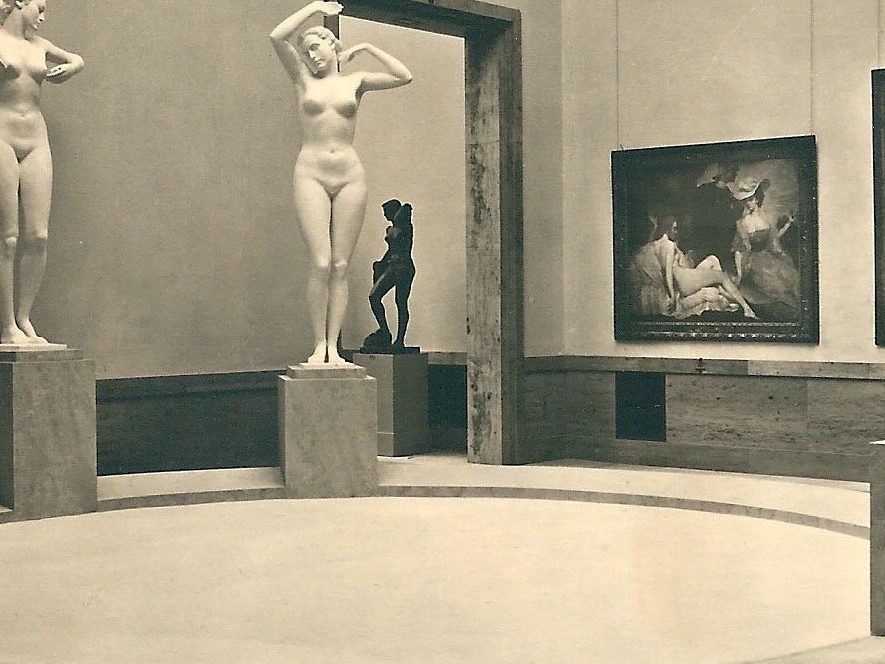

When looking at the exhibition catalogues and visual documents from these shows, it is obvious that, for the most part, the exhibits were stylistically committed to a conservative academicism as was taught at the relevant institutions since the 19th century. A majority of the exhibits were depictions of landscapes, rural idylls, mythological scenes, and animals, as well as still lifes and portraits, which also sometimes demonstrated the influences of New Objectivity. Portraits of Nazi leaders were in the minority but placed in strategically significant locations. Adolf Hitler’s portrait was an obligatory presence and was meant to attract the visitors’ attention as soon as they enter the first room. A neo-classic style dominated the sculptural works, which - here Arno Breker and Josef Thorak come to mind - bordered on the militant heroic. After the outbreak of the Second World War, depictions of soldiers and war, which served a clear propaganda purpose, assumed a special status. In contrast, there were numerous, mostly hyper-realistic nudes that embodied the so-called “Aryan” type.

![“Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” 1940. Hall of Painting in the west wing of the building. In the background: Josef Thorak’s “Frauenakt” [Female Nude] © Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte, Photothek](https://www.hausderkunst.de/uploads/fragments/images/Import/_artPracticeFullWidthImage/GDK_5_2023-06-20-153844_qodw.jpg)

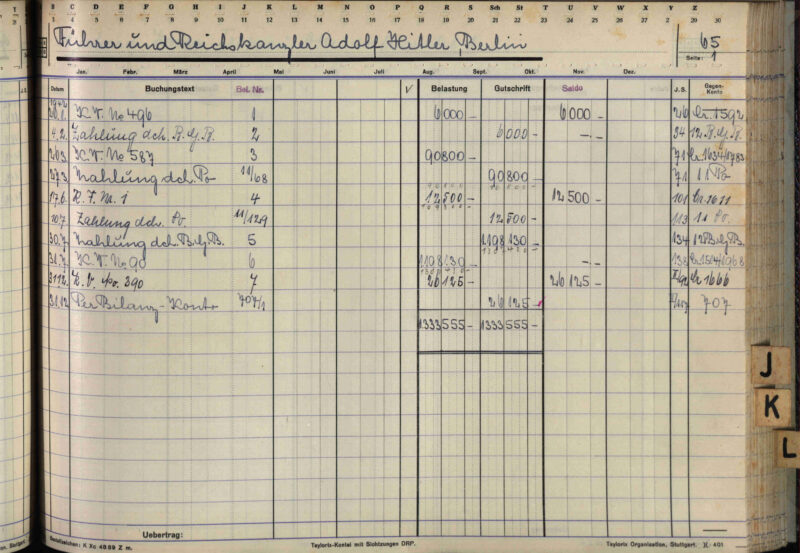

It is only since 2004 - in the course of researching and opening Haus der Kunst’s Historical Archive – that we have had access to detailed information about the purchase policies and economic matters of the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen.” From 1938 onward, submissions were recorded in an artist's register and sales in the ledgers of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst. The ledgers provide information about the works sold, their purchase price and their date of sale. The ledgers also provide precise insights into the identity of the buyers. Since October 2011, this information has largely been accessible via the online database gdk-research, which was developed by the Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte in cooperation with the Deutsches Historisches Museum and Haus der Kunst. In addition to the information from the legers, the foundation of this first research platform dedicated to art under National Socialism consists of six photo albums, in which the ”Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen“ from 1938 onward were documented by the Munich photo studio Jaeger und Goergen. Only about ten percent of the works exhibited in these shows were previously known from images.

A total of 12,550 works of sculpture, painting and graphics were exhibited in the eight “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen;” more than 7,000 of these works were sold for a total price of nearly 19 million Reichsmarks. The “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” seemed to establish a market for contemporary “German” art. But it must be remembered that the public supply of art in Germany - following the banning and sale of so-called “degenerate art” and the liquidation wave of Jewish galleries and auction houses - was largely restricted to art that the Nazi regime also deemed as such. At the same time, the top party leadership also dominated the market as a buyers. Adolf Hitler’s purchases alone accounted for around 6.8 million Reichsmarks.

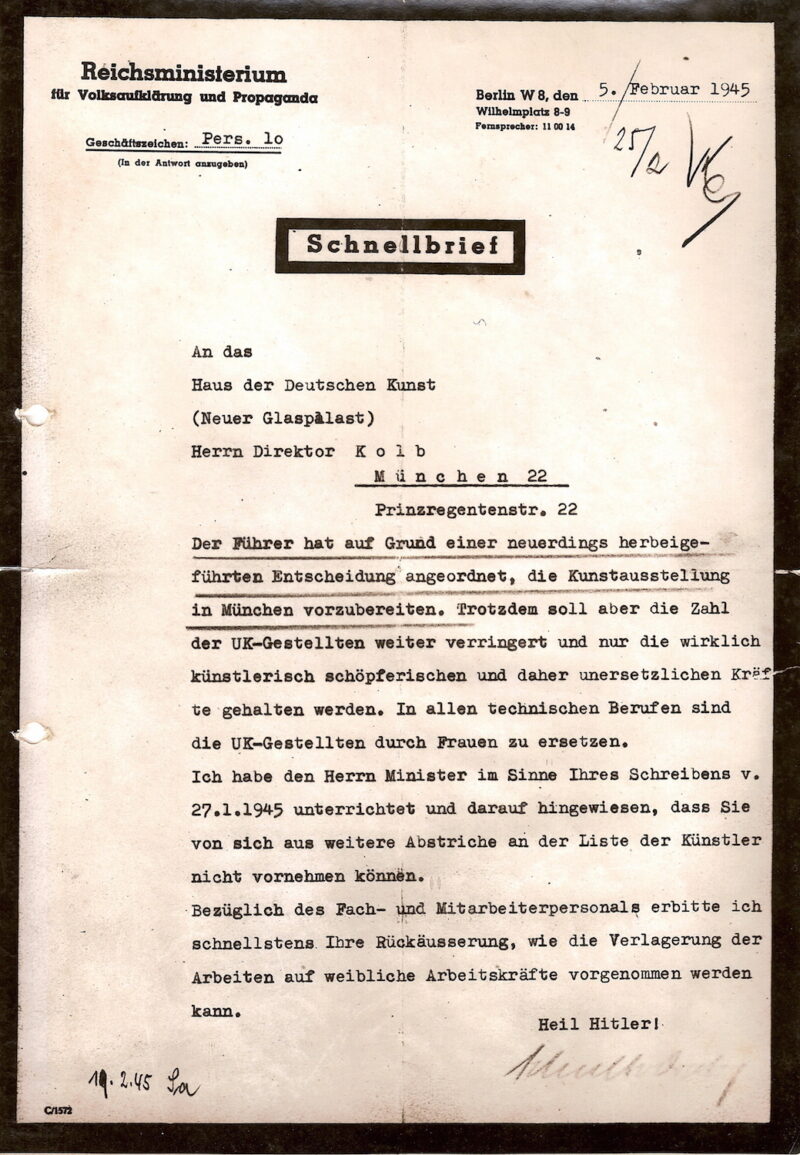

It was not only the top brass of the National Socialist party and their organizations who were among the buyers at the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen;” private individuals also flocked to the Haus der Deutschen Kunst in large numbers. Between 1937 and 1943, the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellungen” recorded an average of 600,000 visitors annually. The eighth and last “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” still attracted 80,000 people; motives for visiting the Haus der Deutschen Kunst varied, from enthusiastic agreement with the Nazi state and its art policy to apolitical leisure activities. In addition, the successive outsourcing and closing of public art collections because of the war probably also benefited the number of visitors to the Haus der Deutsche Kunst. In order to organize the exhibitions on a large scale even during the war years, nearly all employees of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst were exempted from military service. In February 1945 Hitler ordered preparations for another “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung,” which, however, was not realized because the war ended.

In October 1945, the US military government commissioned former employees of the Haus der Deutschen Kunst with winding up the remaining paintings and sculptures left in the building. At least 67 paintings were hung in the Officers’ Club in the former Haus der Deutschen Kunst. From August 1946 onward, the works still stored in the building’s depot, including the purchases made by various Nazi ministries, were transferred to Munich’s “Central Collecting Point,” the largest central collection point in southern Germany for objects of Nazi art theft, and subsequently relocated numerous times. The works were returned to the artists or purchasers only if they presented a political clearance certificate (denazification court ruling). In 1963, the US government handed over some of the paintings and sculptures purchased by Hitler to Munich’s Higher Financial Directorate, which were then stored in Munich’s Main Customs Office. 35 years later they were transferred to the Deutsches Historisches Museum to Berlin.

Branded by a history people were at pains to repress, the artistic records of the Nazi era in post-war Germany were tabooed and stored away. Although there has been a major shift to view them from a documentary perspective these days, the public debate surrounding these works remains still difficult, not least with the regard to museum’s presentation and scholarly research as well as a related revision of our image of art under National Socialism.

Sabine Brantl is Curator Archive and Head of History Department at Haus der Kunst. As curator, she is responsible for the exhibitions in the Archive Gallery. In 2007 she published the first comprehensive monograph on the history of the institution: Haus der Kunst, Munich. A Place and Its History under National Socialism, published by Allitera Verlag München.