This blog post outlines the discourse between Michael Armitage’s works and European art history.

In addition to artists such as Meek Gichugu, Sane Wadu, Jak Katarikawe and Theresa Musoke, who were active in the genre of East African figurative painting between the 1970s and 1990s, Michael Armitage’s works also engage in a dialogue with works by famous painters of Western art history. Thus, Armitage’s paintings may appear strangely familiar to the eye trained in European art history, prompting a feeling of déjà-vu.

The iconography of Titian, Francisco de Goya, Édouard Manet, and Paul Gauguin can be found in the artist’s compositional elements, motifs, and color combinations. Raised in Kenya, Michael Armitage adeptly thematizes the European perspective and the associated exoticism of regarding the “other” while simultaneously heightening our awareness of the repercussions and legacy of colonial attitudes, particularly in the context of our own aesthetic preferences and viewing habits.

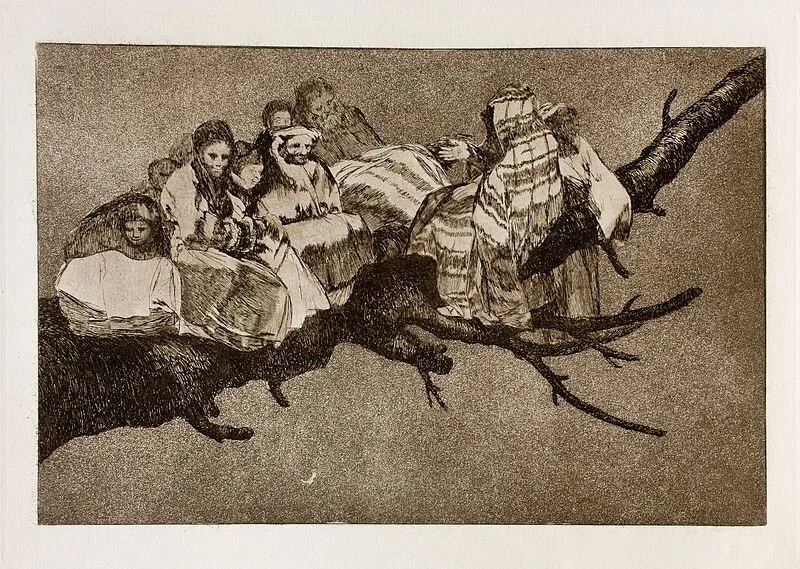

Michael Armitage’s “The Fourth Estate” (2017) inspired by Goya

Francisco de Goya was an inspirational artist for Michael Armitage’s execution of “The Fourth Estate,” and Armitage has integrated the Spanish painter’s pictorial concepts into his artistic practice. Both Armitage’s painting “The Fourth Estate,” and the old master’s etching “Disparate ridiculo” (Ridiculous Folly, ca. 1820) depict a group of figures sitting on a large branch under which a crowd has gathered. In Armitage’s “The Fourth Estate” several figures have taken their places in the tree’s sweeping crown; here, however, their attention is focused on an event taking place in the background, off in the distance. Parallels can also be drawn in both formal and contextual terms between Armitage’s work and Goya’s graphic series “Los Disparates” (The Follies), which critically examines the political conditions in Spain in the early nineteenth century.

Michael Armitage executed his “Kenyan Election Series” between 2017 and 2019. The cycle comprises a total of eight paintings created by Michael Armitage following an election campaign event in Uhuru Park in Nairobi. Located in the heart of Kenya’s capital, the park has been a site of major political events since the 1970s. During Kenya’s 2017 presidential election, Armitage attended a rally organized by the opposition party, whose top candidate, Raila Odinga, was challenging the incumbent Kenyatta for the fourth consecutive time. Because Odinga questioned the legitimacy of the previous election’s results, there were riots and protests throughout the country. Michael Armitage places these protests in the center of the painting with visual impact. Like the previous one, the 2017 election also went to the President Kenyatta. The mood in Uhuru Park and on the streets of the capital was chaotic and marked by unrest and mayhem. Back in his studio, Armitage transformed his observations into often puzzling scenes in which some people wear green wigs and, instead of political statements, larger-than-life toads are displayed on banners.

The Laocoön Group in the painting “Nyayo” (2017)

The center of Michael Armitage’s painting “Nyayo” is occupied by the figure of a muscular, naked man with a snake twisting around his right calf. This figure is immediately reminiscent of the famous Laocoön Group in the Vatican museums, an ancient sculpture group depicting the myth of the agony of the priest Laocoön and his two sons inflicted on them by snakes emerging from the sea. In art history, the representation of the pain in the marble group has been especially praised; while pain is evident in the muscles and tendons of the Laocoön’s body, the priest does not exhibit this pain with a scream, but rather bears it silently.

The title of the painting “Nyayo” literally means “footprints.” This word was used by the autocratic ruler Daniel Arap Moi as an election slogan. When he took office, a government and administrative building in Nairobi was named “Nyayo House.” The building is now infamous for its underground detention cells, in which critics of the regime were imprisoned and tortured in the 1990s. According to eyewitness reports, the Moi regime had snakes brought into the cells in order to persuade political opponents to confess. The prisoners had little choice but to assume the snakes were poisonous.

The composition of Titian’s “The Assumption of the Virgin” (1516-18) in the painting “Pathos and the Twilight of the Idle” (2019)

The composition and coloring of Michael Armitage’s painting “Pathos and the Twilight of the Idle” recalls a famous painting by the Venetian artist Titian. Born as Tiziano Vecellio, Titian had been a master of Venetian painting since the day his teacher, Giorgione, died in 1510. Titian completed his first recognized masterpiece “The Assumption of the Virgin” in 1518. The work, an enormous altarpiece measuring 690 x 360 cm, is still situated in its original location, on the high altar of the church of Santa Maria dei Frari in Venice. “The Assumption of the Virgin” made Titian a sought-after master of composition, bold colors, and high drama. In Armitage’s “Pathos and the Twilight of the Idle,” however, tear gas and billows of smoke rise into the heavens instead of angels and clouds.

A baboon assumes the pose of Édouard Manet’s “Olympia” (1863)

In Armitage’s animal paintings, monkeys appear as scrutinizing reflections of humans. As cross-border creatures, they embody the interrelationship and overlap of human and animal characteristics. In the painting “Baboon,” one of these apes is presented in a seductive half-reclining pose that is vaguely reminiscent of Édouard Manet's provocative Olympia figure in his eponymous painting (1863). In the nineteenth century, the painting “Olympia” drew attention to the power of the gaze in an unusual and radical manner. In “Baboon,” the animal’s long, outstretched extremities appear almost human. Yet, in contrast to Manet’s painting, in Armitage’s work a lush banana tree, rather than a hand, covers the baboon’s groin. With this, Armitage propels the clichéd images and sexual fantasies with which the black male body is still associated into caricature.

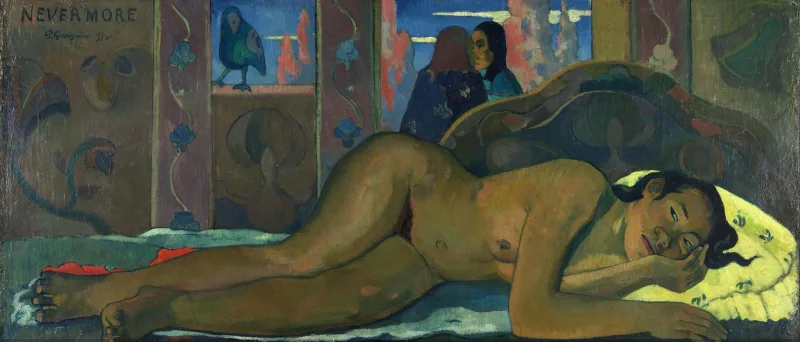

The nude by the French painter Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin in the work "The Promised Land" (2019)

“The Promised Land” depicts a marching, roaring crowd, which recalls the chaotic and unmanageable scenes of violent demonstrations during the 2017 elections in Kenya. A flag stands out from the painting’s background, revealing a reclining female nude. This figure inevitably brings to mind the painting “Nevermore” (1897) by the French painter Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin. Like many of Gauguin’s works, it embodies an exoticizing aesthetic, in which the Western view of the (female) non-European “other” manifests the equally fascinating and disconcerting unknown. In Gauguin’s work, the foreign, South Pacific island of Tahiti – the inspiration for so many of his works – is stylized as a colorful counterworld to the artist’s dreary life in Paris. An exotic natural paradise, it is portrayed as a place of refuge, where one can break free from the constrains of bourgeois life. For Gauguin, the portrayals of the island, imagined as paradise and sanctuary, are, above all, images of his own projections embedded in a historically evolved power imbalance. In his artistic gesture of appropriation and reinterpretation of Gauguin’s exotic imagery, Armitage reverses this relationship. At the same time, “Nevermore” – in the tradition of the female nude, which also embodies the power of seduction – explores the male view of the naked female body. In Armitage’s painting, however, the recumbent female nude on the flag, the iconic female on display as an “object of desire,” obtains a new meaning in the context of the artist’s interest in the temptations that are integral to the dissemination of simple truths, seductive promises, and political ideologies prevalent in propaganda.

Would you like to learn more about Michael Armitage's works? Then order the exhibition catalog or watch the video Meet the Artist - Michael Armitage.

The blog post on the aforementioned East African artists can be found at:

Mwili, Akili na Roho – East African Figurative Painting of the 1970s — 90s