Walther's artistic approach radically expands the spectrum of the artistic practice itself: the human body becomes material and part of the activation. In her essay Jana Baumann describes Walther‘s early urge to overcome the passive role traditionally assigned to the viewer and to explore a new presence of the body and physical sensation in the visual arts.

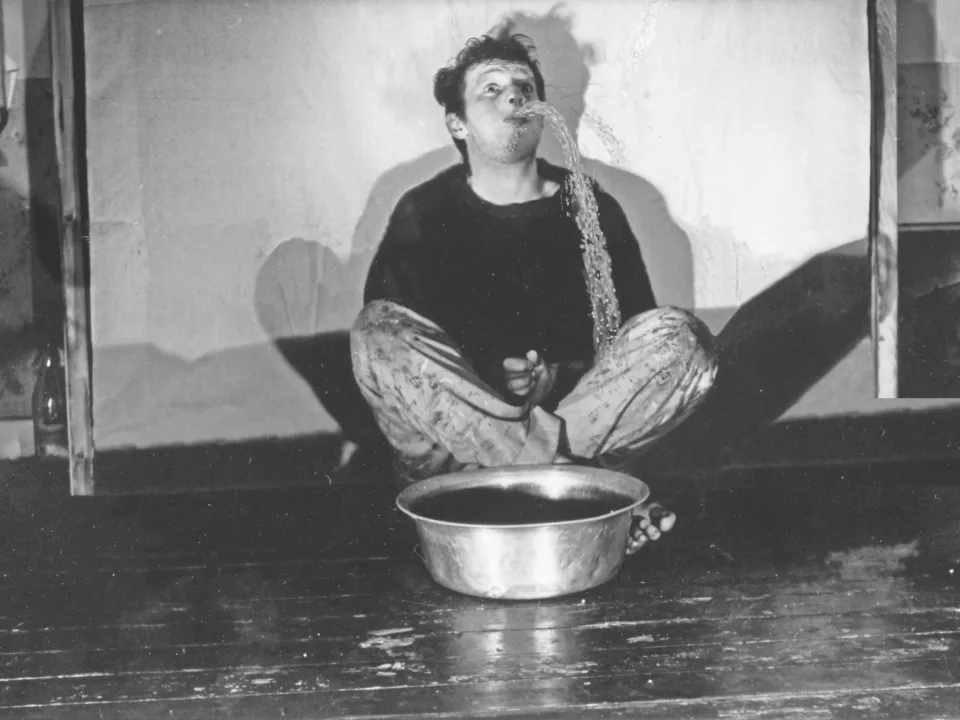

A young man with dishevelled hair and clothes covered with splotches of paint sits cross-legged and barefoot in front of a silver bowl and, with his head held high, spits out a mixture of flour and water. Franz Erhard Walther titled the photograph of this first action at the age of nineteen Attempt to be a Sculpture, Gargoyle (1958). This early work already contains the entire essence of Walther’s future work and his radically expanded range of artistic practice. In the viewer’s mind, the figure of a sculpture carved in stone emerges; Walther, however, already infiltrates this notion with a living image of himself as a protagonist.

The body serves him as a medium, and its action leads to a living being becoming an image, so to speak. With this image, Walther appeals to the viewer’s imagination. From the very beginning, he has always dedicated himself to the opposites of material and immaterial, subject and object. He thus became a key figure in the conceptual renunciation of the image driven forward by the European postwar avant-gardes; at the same time, he established a substantially expanded understanding of the image that is still valid to this day.

The beginning of his oeuvre, which spans more than six decades, was marked by the gesture of a radical iconoclasm aimed at revising the narrative strategies of modernity. With Yellow and Blue (1963), two non-returnable glass bottles filled with bright blue and yellow pigments, he achieved the abolition of painting by non-painterly means. The work served to visualise an idea by questioning—in the spirit of conceptualism—the triad of object, picture, and image.In doing so, he symbolised the overcoming of the handcrafted work of artHe raised the elements of body, space, place, time, and language to his artistic means, with textiles and colour serving as his vehicles.

The artist stated in retrospect: ‘My work as a whole, which—on the one hand: unfortunately, and on the other: thank God—is still, for the most part, not seen in the proper light, is ultimately an assassination attempt on art. My work makes deep cuts into basic ideas, conventions and ways of thinking about art, that is to say, at its roots’.

The urge to overcome a passive and privileged bourgeois concept of the viewer manifested itself. It was here that Walther’s primary artistic goal took form: to confront art with life—to create spheres of circulation.

In his early years, which were characterised by a great joy in experimentation, Walther thus lent vividness to an almost inexhaustible variety of pictorial concepts. He strove to rebel against an overpowering, dominant authorship—such as that which is tangible in the cult of the genius—in the earliest material processes using coffee, vegetable oil, glue or soy sauce on paper and cardboard, whereby the principle of chance generally determined the pictorial composition. In the end, however, the processual and the action became established as constants within his oeuvre as a whole.

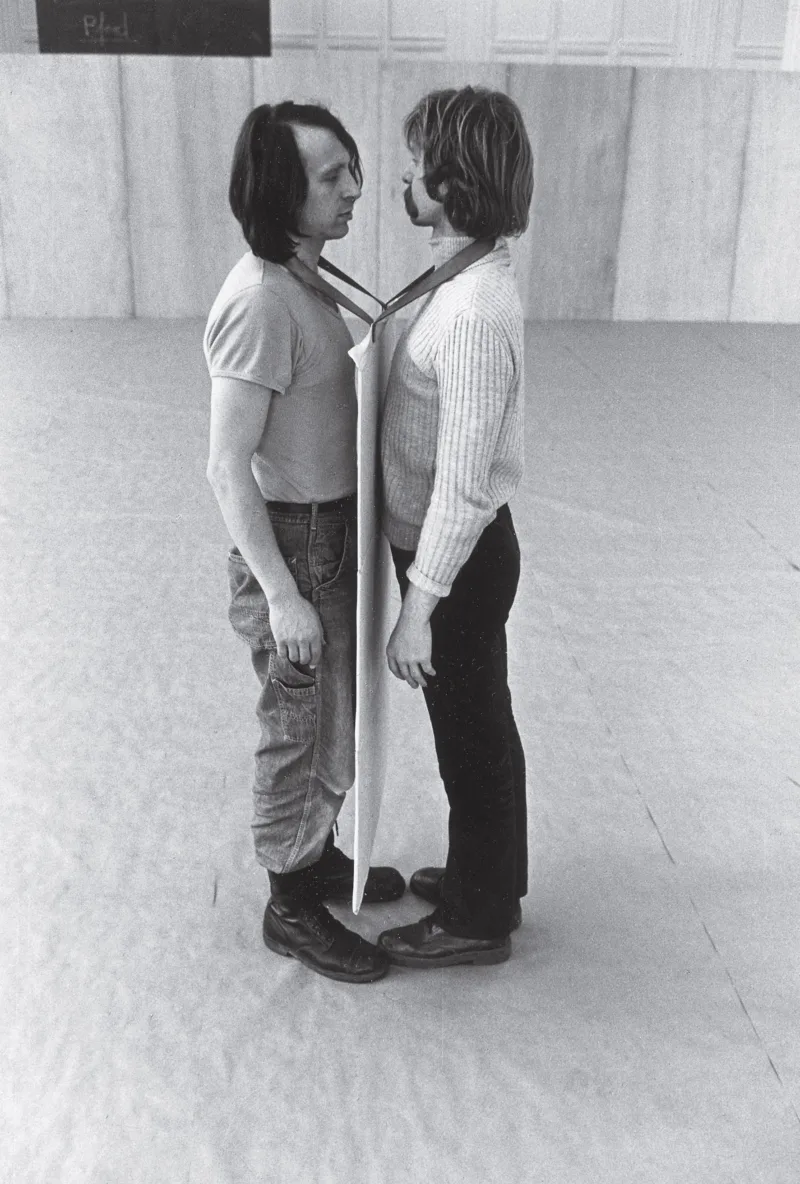

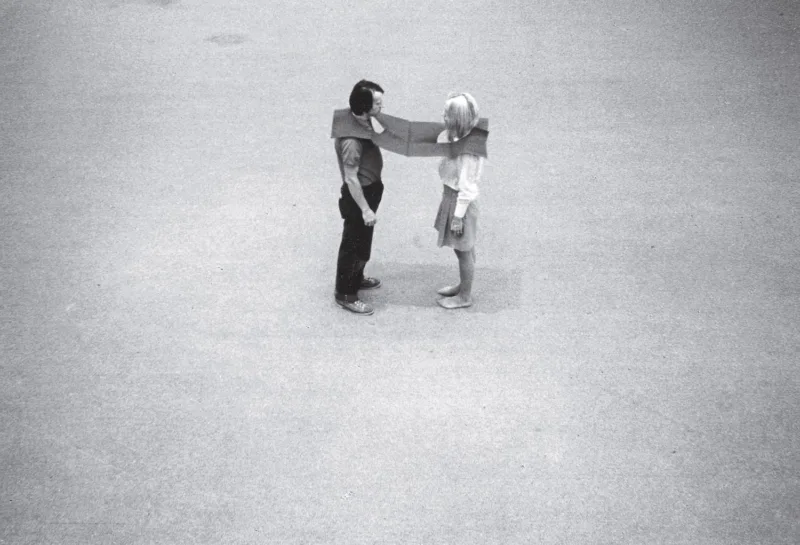

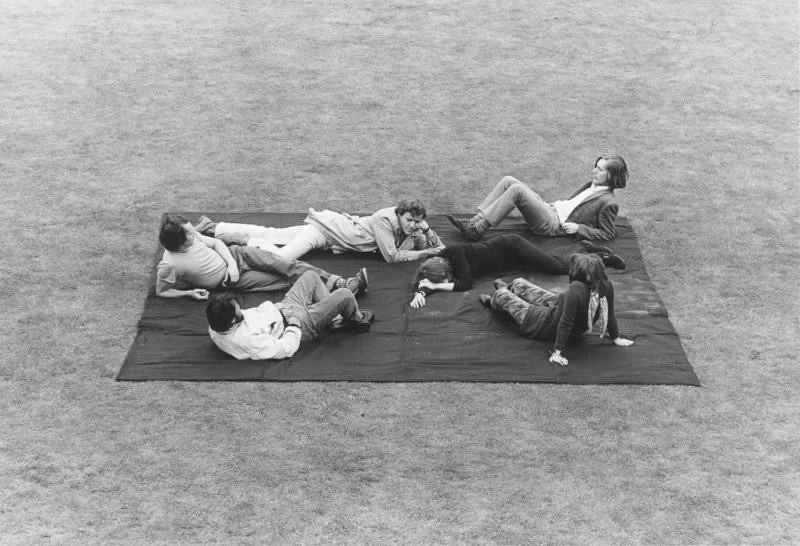

Walther’s breakthrough regarding the participation of the viewer occurred in 1963 by liberating him from his traditionally passive role. With the Handpieces, Walther achieved a sensitisation of perception—as in Two Ruby-Coloured Velvet Cushions (Filled and Empty) (1963), by feeling and sensing different volumes. With the First Work Set (1963–69), Walther specifically addressed the mind and one’s own self, as well as one’s vis-à-vis. Connected with this was the discovery of sewing in 1963; since then, the objects have been made by his at that time partner and later first wife Johanna Walther. Walther came into contact with the craft of sewing through Johanna and her parents’ tailor shop. What all fifty-eight pieces of cotton fabric in the First Work Set have in common is that they invite the viewer to take action. They are to be held, stretched or pulled by one or more persons. Pieces such as Closeness and For Two are characterised by a strong intimacy due to the constant closeness of the vis-à-vis. Gathering also creates a loose, informal meeting of individuals on a square cloth. The interactive workpieces thus initiate extraordinary interpersonal situations. This triggers a diverse spectrum of thought, perception, and emotional processes in the user. During the activation of the pieces, a subtle communication takes place, which has been defined by the artist in its key points and conceived as a transformational event.

Participation, co-determination, self-responsibility, and decision-making were topics of a social discourse that revolved around a more humane reality of life. So the artist used the public sphereas a medium for interventions that addressed its constitution and demanded authority-free discourses based on equality.In addition, a further form of pictoriality emerges from the work actions, in that the formal representations can attain pictorial expression. Walther stated in retrospect: ‘The work concept changed in the early 1960s. After all, in order to gain a certain distance from history, radicalism was necessary, also with regard to genres. I had to do away with the frame and the pedestal in my work; I had to give the picture a different meaning, to question the concept of sculpture’. This statement once again reveals how central the liquefaction of genre boundaries has been as a motor for Walther’s thinking. The human body became an experiential body, whereby the work activities were not limited to the premises of galleries or museums. Walther conquered the outdoor space for himself.

This was followed by demonstrations of elements from the First Work Set, for example in the auditorium of the Düsseldorf Academy of Art in 1964, with the participation of artist colleagues such as Sigmar Polke, and in the presence of Blinky Palermo and Joseph Beuys, as well as at the exhibition Frisches in the flat of Jörg Immendorff and Chris Reinecke in 1966, where activations were carried out together with others, including Nam June Paik or Charlotte Moorman. Nevertheless, the response to Franz Erhard Walther’s work was marked by a great deal of incomprehension, which prompted him to move to New York with his wife Johanna in 1967. Walther recalled in retrospect: ‘Everything had become so cramped in Düsseldorf. This small-mindedness, the squatting on top of each other and talking badly about the others. I didn’t like it anymore. Two great paintings by Barnett Newman that I had seen at the second documenta in 1959 represented America for me: the freedom, the greatness and also the generosity. This, too, I found in New York’. Here, he would conceive another seventeen pieces for the First Work Set before declaring it complete in 1969. In New York, Walther encountered an art scene in which conceptual, temporalised, and dematerialised working methods were omnipresent.

It is iconic works that have made Walther a point of reference for today’s generation of performative artists, who declare the body to be their material and create situational, action-oriented, and ephemeral works with a pictorial character.

The Wall Formations are of key importance in the genesis of Walther’s work. With them, Walther carried out the radical intertwining of painting, sculpture, and architecture, the design of which is always based on human dimensions. The starting point of this body of work was the Yellow Sculpture (1969/79), the early conception of which manifested itself in the flatness of the work. Here, Walther apparently took up considerations that had already underpinned his oldest wall works that denied any illusionistic representation, such as Two Yellow Boxes (1962/63) and 12 Wrapping Paper Gluings (1963). It is first and foremost about the fruitful relationship between form and colour, sculpturally and pictorially ambiguous figures. By developing elements that can be worn or entered, Walther transforms the body into a module and means of representation. In this way, the viewer’s understanding of traditional pictorial logic is challenged. With their bright colours ranging from red, yellow, and black via green to ochre, as well as the natural-coloured muslin as the base material for the painting, the Wall Formations may recall monochrome paintings, thus exemplifying Walther’s repeated focus on the wall. Yet their monumental size and spatial volume also convey sculptural aspects. The activation opens up a wide range of possibilities, which is why the appearance of the formations remains mutable—but which, in its simultaneity, is never tangible. Within each Wall Formation, Walther created complex internal formations recalling architectural fragments with, for example, column forms or cornices. Wearable coats, sleeves or waistcoats serve as a shroud for the protagonist and interconnect body, space, and architecture. Franz Erhard Walther once commented on this: ‘The picture was to be given a different meaning, the concept of object art and sculpture became liquefied’

For the Wall Formations, Walther used colour conspicuously as an essential compositional tool and also began to use the colours already found in his early Word Images for the textile works. Walther met Andy Warhol in New York on several occasions; his fellow students Gerhard Richter and Sigmar Polke also dealt in their panel paintings with the increasingly commercially orientated society. In contrast, Walther himself never turned to representational imagery; nevertheless, the intense primary colours of Pop Art continue to determine his work to this day.

Walther thus broke with outdated principles of style and traditional artistic procedures. He turned his back on the representation of the image and focused instead on the presence of the body and tactile feeling. In doing so, he forced the shifting of boundaries within the field of tension between the organism and the image, between movement and standstill. Under the guiding principle of the body as the interface between mind and matter, Franz Erhard Walther lent clarity to a media reflection of historical significance.

Jana Baumann is senior curator at Haus der Kunst and curated the exhibition "Franz Erhard Walther. Shifting Perspectives".