This is a shortened version. The entire text can be found in the exhibition catalogue of “Rebecca Horn”.

[…]

Spanning six decades, Horn’s transmedia oeuvre explores life against a back- drop of blurred boundaries between nature and culture, technology and biological capital, the human and the nonhuman. Whether the artist is described as an inventor, director, author, composer, or poet, she considers herself first and foremost a choreographer. Horn describes her practice as a precisely calculated orchestration of space, light, physicality, sound, and rhythm. Becoming a machine, an animal, or even the Earth, a process which occurs in her works, is aimed at the stimuli of a visible, tangible, and audible existence that can be physically experienced—an incarnated understanding.

In one of her earliest drawings, Lips Machine (1964), made when she was only twenty, Horn addresses the body as a means of artistic expression. The feminized red lips appear as an organ radically deprived of its body, as well as spatially measured and trapped in lines reminiscent of a medical drawing. Here, the body can be experienced as a disciplined and powerful material to be controlled. The openly visible permeability of physical boundaries makes the individual body a threatened one. It is a human-machine relationship reminiscent of dystopian science fiction, the control of which is already the responsibility of an artificial intelligence of sorts. The use of muscle power evokes images of a preindustrial era—or are we already in the future?

But the body can also be seen as a unifying element. It is bodily affective and capable of communicating, of conveying feelings. It is always in a state of flux between dependence and independence in the experience of others and the other. It is capable of suffering pain, experiencing pleasure, feeling fear, and developing resistance.

[…]

In the early 1970s, with Performances I (1972) and II (1973), Horn moved beyond the theme of controllability to that of the extension of the body, using wearable sculptural cotton and material constructions to create unfamiliar perceptions. The extensions influence the wearer’s movements and expand their physical boundaries, accompanied by an extreme sensory experience. The resulting movements are of fantastic grace or suggest pain, as in Unicorn (1970– 72), which the artist presented at documenta 5 (1972) at the invitation of Harald Szeemann.

[…]

The performances expose the human body to processes through which embodied knowledge is generated. Extensions such as the Head Balance (1972) and Moveable Shoulder Extensions (1971) allow for extraordinary physiological experiences. Other objects, such as Head Extension (1972), require several people to maintain the balance of the performers. Through the traction exerted by cords, one’s own posture is balanced between control and self-control. In this way, reality and the imaginary intertwine in physical and movement images that trigger contemplation, perception, and memory. With these historically significant performances, the artist addresses the human body as a repository of knowledge, and also consciously addresses the body’s memory, as it is practiced in dance technique. Movement thus becomes an experience that is already decoded in the process of its encoding. Horn defines the execution of the movement but seeks individual information about the body. The focus is on a poetic and social understanding of the body that reveals its relationship to the influences that shape it, while at the same time allowing them to be suspended.

[…]

With the dialogical coexistence of performers and audience, Horn begins the manifold stagings of perceptual relationships in her oeuvre. Supposed logics of the relationship between inside and outside are made tangible in their contradictions and significance. Horn uses the extensions to show how the energy of our bodies is connected to the surrounding space. The newly digitized film footage of the early work in its large-format presence as an exhibition opener conveys how we inhabit our bodies and in what way bodies are transformative. Here, a kinetic shift into the interior takes place, a leitmotif of all of Rebecca Horn’s subsequent work.

[…]

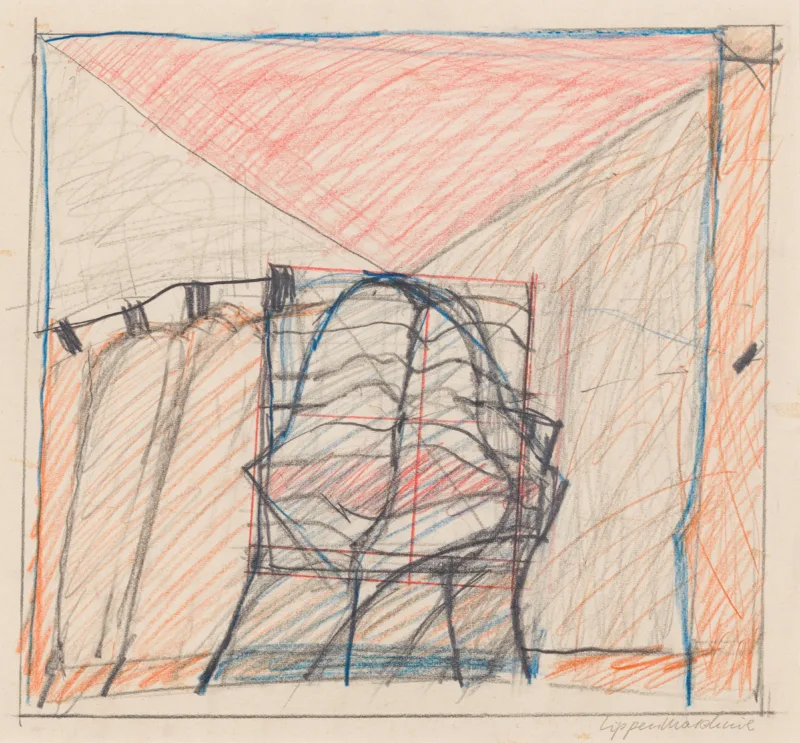

Her studio in New York, converted into a ballet studio—she lived alternately in New York and Berlin for over a decade starting in 1972—served as the film set for Der Eintänzer (1978). Fantastic scenes take place there, where ballet is omnipresent in the film’s plot, but especially in the scene with the exercises of the young dancers, who, connected to each other by strings, submit to a mechanistic control of their movements. Here, the person is no longer at one with their body, a programmatic symbol. In the exercises aimed at perfection, the individual recedes into the background. The desire for absolute synchronicity is reminiscent of the leveling of human and machine within the framework of efficiency-oriented forms of economic organization and disciplinary regimes in late modern capitalism, as described by Michel Foucault in Discipline and Punish (1975). Here, dance is not an expression of the dancers’ individual feelings but adapts in terms of form to the will of the choreography. Horn uses the symbolic content of dance movements as a medium and catalyst for her choreographic fictions. With a kind of mood board for the project, the work Untitled (In this room ...) (1977) shows the great importance of dance as an inspiration and as a part of her biography and, equally important, the early experience of illness. For Rebecca Horn, standstill goes hand in hand with movement; she is fascinated by contrasts and contradictions.

[…]

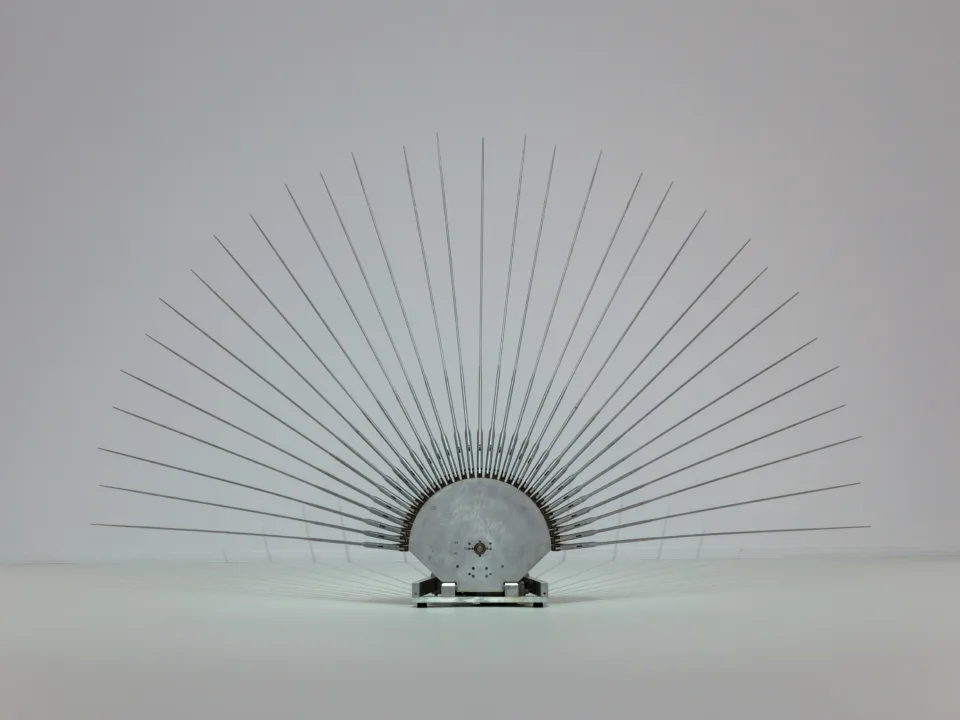

In Rebecca Horn’s work, film is an important resource and a powerful moment for working with choreography. The dancers in the film represent a preliminary stage to the later movement machines. Like industrial processes, Horn’s choreography breaks down work and exercise sequences into individual elements. Through the rhythmic repetition of moving sculptures, she creates symbolic figures as in dance practice.

[…]

It is therefore not surprising that, in her feature-length films, she also skillfully combines different levels of perception through the beings she portrays, be they objects, humans, or animals. Her last feature film, Buster’s Bedroom (1990), is set in the “Nirvana House,” a psychiatric hospital in California. Through these fictional patients, Horn conveys complex feelings and multilayered perceptual relationships. In doing so, the artist once again challenges and circumvents categories such as “healthy” and “abnormal.” Instead, she celebrates the power of the imagination and dedicates the film to one of her inspirations, Buster Keaton, who was once a patient at Nirvana House. The work can be read as a protest against state control and the social discrimination against bodies.

[…]

Rebecca Horn’s oeuvre is a lifelong and currently vibrant echo of the progressive decentering of the human being. She explores the interaction of the senses and uses performativity to place the sensuality of the body in relation to the environment at the center of her work, searching for new ideas of community in a cosmic whole.