In her seminal book, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (1985), American essayist Elaine Scarry wrote that “whatever pain achieves, it achieves in part through its unshareability, and it ensures this unshareability through it resistance to language.” This relationship between pain and representation continues to fascinate and trouble us. Should art convey the pain of others and offer solutions to moments of crisis?

This essay looks back at a selection of recently exhibited works at Haus der Kunst by Adriana Varejão, Noel Ed De Leon, Khvay Samnang and Njideka Akunyili Crosby which investigate the notion of ‘healing’. The artists look beyond healing as recovery from physical trauma, and instead turn to global history, politics, culture and economics. In doing so, they explore how the ability to empathise with another’s hardship is not objective, but is deeply guided by representations - photographs, films and artworks - which speak from the histories, experiences and agendas of their makers.

Adriana Varejão (b. 1964, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) delves into the layered histories of Brazilian culture, identity and colonial trauma. In many of her works, she deploys recreations of crafts, most notably decorative Islamic-inspired terracotta tiles, or azulejos, which were imported by Portuguese colonisers. These represent the vast exploitation of Brazil’s natural resources, while highlighting traces of colonial cultural influences, as well as racial and economic divisions in present-day Brazil.

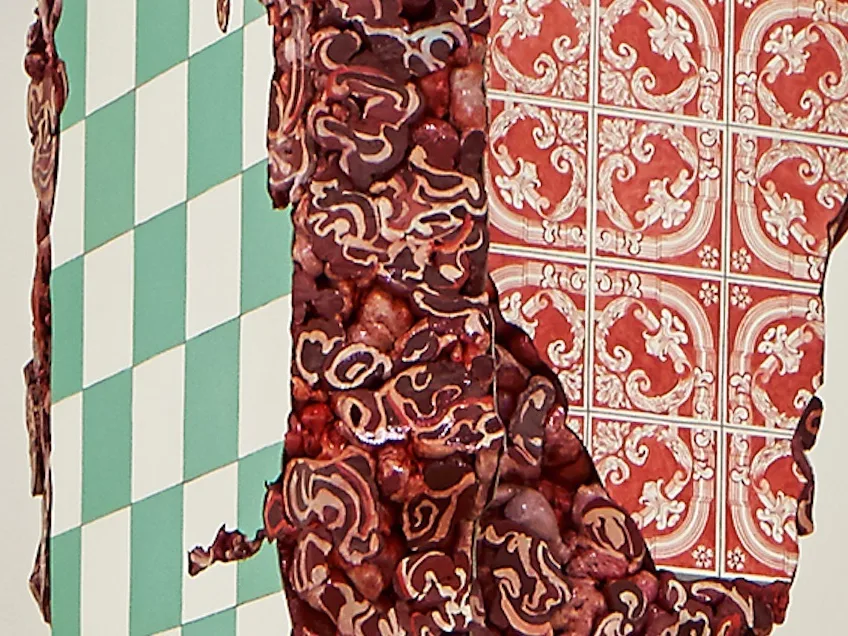

These tiles reappear in the sculpture Linda Da Lapa (2005) recently featured in the group exhibition Interiorities (2019-20). Linda Da Lapa portrays a partially demolished wall whose interior is made of undefined flesh. This work belongs to a series of sculptures titled Jerked-beef Ruins in which the artist presents compact flesh within crumbling edifices. It differs from another of Varejão’s series, Tongues and Incisions, in which organs violently rupture, tear and burst from walls.

In contrast, Linda da Lapa offers an image of wholeness; its meat-like interior (it remains unclear whether this is human or animal) evokes a support structure, rather than pain and suffering. This suggests a hopeful, yet tentative understanding of ‘healing’; here, human compassion, labour and co-operation are the ‘building blocks’ of present-day states and societies. Yet, these are susceptible to national politics and global economics.

A similar interest in the intertwining of bodies, nature and infrastructure is also central to the work of London-based artist Noel Ed De Leon (b. 1976, Pangasinan, Philippines). In 2019 de Leon staged a live performance, Feast of the Predator, as part of the exhibition Archives in Residence: Southeast Asia Performance Collection. In a ritualistic and military-like ceremony, the artist first dragged a bundle of fur coats across Haus der Kunst’s middle hall. He then installed these inside the Archive Gallery, adorning them with artifacts from Second World War gathered from the Philippines, Britain and the depot of Haus der Kunst.

Feast of the Predator deployed animal fur as a symbol of status and protection, as well as authority and aggression. In the performance, these associations spoke to the legacies of American military and economic interventions in Germany and the Philippines after the Second World War.

Through gestures such as scattering original American military cutlery in the entrance of the Archive Gallery, de Leon drew connections between differing trajectories of the U.S.A.’s intervention as a force of international ‘healing’; from Haus der Kunst’s repurposing as a mess hall for American troops after 1945, to the U.S.A.’s annexation of the Philippines from Spain at the end of the 19th century, and its exertion of neo-colonial influences in the Philippines after liberating it from the Japanese invasion during the Second World War.

Performed from de Leon’s own position as a Philippine diaspora artist, Feast of the Predator investigates ‘healing’ through the lens of national recovery. For de Leon, however, this entails not only the rebuilding of infrastructure, but also sees new, fraught political and economic dependencies come into being.

In a similar vein, the two-channel video work Popil (2018) by Khvay Samnang (b. 1982, Svay Rieng, Cambodia) presented as the 10th ‘Capsule’ exhibition at Haus der Kunst in 2019, also explores the role of intrastate politics and economic relations in national healing.

Popil depicts two dancers wearing hand-woven dragon masks. They perform a contemporary rendition of a classical Khmer rain and fertility ritual dance. This is reinterpreted here as choreography on the theme of love and courtship. However, this does not refer to the connection between individuals. It rather references the long-standing cultural and economic ties between Cambodia and the Peoples Republic of China who are each represented here by the respective dragons.

As the dancers move across jungles, swamps and the coast, one catches glimpses of cities, settlements and industry in the background. These hint at Cambodia’s need for social, economic and cultural healing in the aftermath of the enormous divisions wreaked by the Civil War of the late 1970s. Yet, they also highlight Cambodia’s increasing economic dependence on China over the course of this recovery.

While China and Cambodia have long shared cultural ties, recent years have seen China increasingly fund infrastructural projects with often unclear, disadvantageous or exploitative conditions for Cambodia’s natural resources. This topic has been the subject of the artist’s earlier works such as the photo-series Rubber Man (2014). Here, he documented himself pouring liquid rubber onto his body amidst the Northern Cambodia’s scarred forests.

Popil’s outdoor setting references Rubber Man without overtly focusing on environmental exploitation. Instead, its subtle depiction of cities and industries in the background serves as a powerful reminder that (re)building infrastructure in the Cambodian context has been deeply intertwined with the welfare of bodies and beings. The scenes of Popil mirror both de Leon’s caution against the marriage of ‘healing’ and international politics in the Philippines, and Varejão’s depiction of flesh as infrastructure in postcolonial Brazil.

Looking beyond history, Los Angeles-based artist Ndjieka Akunyili Crosby (b. 1983, Enugu, Nigeria) explores entanglements between healing, comfort and convenience, on the one hand, and everyday global inter-dependencies on the other hand. Crosby’s collage-based works return to the realm of private lives and households. These appear filled with utilitarian objects and memorabilia through which the home becomes a layered site of memory and self-reflection.

In the work Garden Thriving (2016) recently featured in Interiorities, a man and a woman modelled on the artist and her husband grasp each other in a casual, yet intimate embrace. They share a chair in a domestic settling where a laptop rests on a table and floral wallpaper covers the background. Revisiting this image in the aftermath of recent global instructions to “stay at home”, Garden Thriving depicts the home as a place of sanctity and protection. Yet, it also shows it as a space laden with references to the outside world and co-dependent histories.

Crosby uses a photo-transfer technique in which she embeds photocopied pictures of family photographs and media images from Nigeria into objects. These become visible when one closely observes surfaces. In Garden Thriving, women’s faces emerge from the wallpaper’s leaves, hinting at the history of the Transatlantic Slave Trade in which people from West Africa were forcefully expropriated to the Americas. Simultaneously, the figure of a woman on laptop’s screen refers to the present-day, reminding us of Nigeria ‘s role as a powerful global production economy.

Highlighted in the word ‘thriving’ in work’s title, Crosby considers ‘healing’ not only as recovery from trauma, but as a continual, ongoing process. As one looks deeper into each depicted object, the household reveals itself a site of ‘healing’ through introspection; each object harbours metanarratives. These tell of historic injustices, as well as coping mechanisms, compassion and exchange.

Seen alongside Adriana Varejão’s Linda da Lapa, Noel Ed De Leon’s Feast of the Predator, and Khvay Samnang’s Popil, Crosby’s work prompts us to think about the ‘healing’ as a return to making something whole again. However, this process of holistic recuperation is one which demands questions into how - and by whom - recovery is told and conveyed. As once noted by philosopher Susan Sontag in her celebrated book, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003) - “no ‘we’ should be taken for granted when the subject is looking at other people’s pain.”

Dr Eva Bentcheva is an art historian and curator with a focus on transnational conceptual and performance art. She was formerly the Goethe-Institut Postdoctoral Fellow at Haus der Kunst (2018-19).

The works by Adriana Varejão, Noel Ed De Leon, Khvay Samnang and Njideka Akunyili Crosby discussed in this essay were featured in the following exhibitions at Haus der Kunst:

Capsule 10: Khvay Samnang (18 January 2019 – 14 July 2019) curated by Damian Lentini;