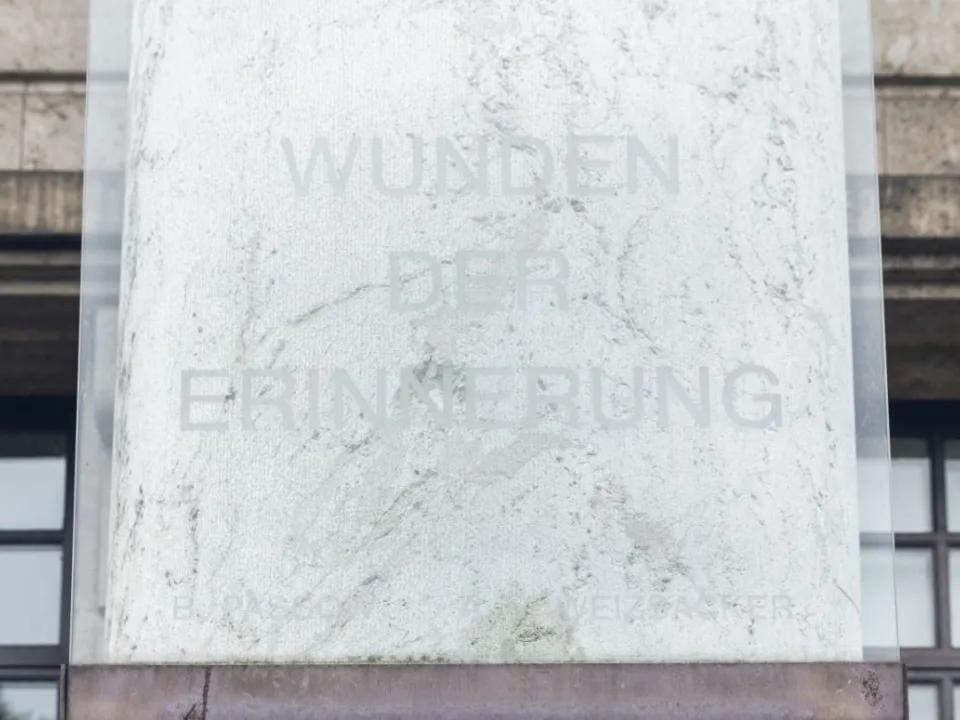

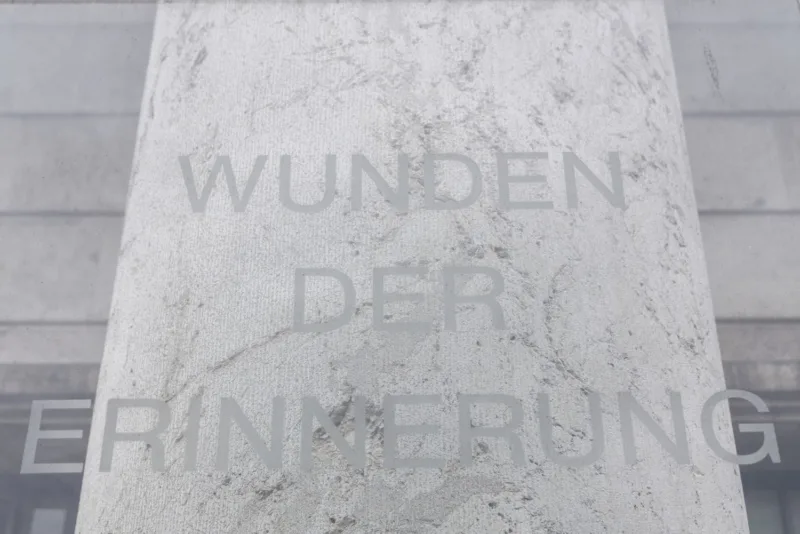

If you walk along the north terrace of Haus der Kunst, you may pass the installation “Wounds of Memory.” The artwork, which is mounted on a pillar at the back of the building, is part of a European-wide project and is a reminder of the scars left by the Second World War; the 75th anniversary of the conflict’s end will be commemorated on 8 May 2020.

“Wounds of Memory” was established in Munich in 1993 during a period in which artists were beginning to participate resolutely in the process of remembering and commemoration with actions and installations, as a way to confront the city's National Socialist past and its politics of remembrance. Rather than providing definitive answers, their projects focused on observing things others had overlooked, exposing gaps and preserving traces of forgetting and repression.

Conceived by Beate Passow (*1945) and Andreas von Weizsäcker (1956-2008), the project “Wounds of Memory” thus began with a search for traces and vestiges. Passow and von Weizsäcker looked for marks left by the Second World War. In Germany and eight countries bordering it, the artists used mass produced square panes of glass to transform bullet holes and other ‘injuries’ left by bomb fragments and grenades into visible scars. Such war scars are rarely perceptible in everyday life today and it is only through this subtle artistic intervention that, as indicated in the title, open wounds are rendered visible. Passow and von Weizsäcker were interested in central structures such as Haus der Kunst, which opened in 1937 as the “Haus der Deutschen Kunst” [House of German Art] and served as the leading institution of National Socialist art policy and propaganda, and in other peripheral public locations. For example, they marked bullet holes on a bridgehead pillar in Rotterdam. In Prague they found books with bullet holes that could be secured after the bombing of the town hall in the final days of the war; in the forest surrounding the Luxembourg municipality of Diekirch, they discovered trees whose trunks had been marred by grenade fragments. The visible scars represent the invisible wounds left by war and its destruction.

The 75th anniversary of the end of the Second World War in Europe is upon us. On 7 May 1945, Colonel-General Alfred Jodl signed the document of the unconditional surrender of the Wehrmacht at the headquarters of the Western Allied Forces in Reims. The surrender went into effect on May 8, 1945 at midnight on all fronts. National Socialist crimes, the unjustifiable injustice of the radical reversal of all human values, gradually became part of the world’s consciousness. That, which no one had wanted to ‘see,’ was now, at the very latest, an unavoidable and blatant reality. Yet, the majority of German post-war society ignored questions concerning guilt and responsibility, cause and effect. The speech by the then Federal President Richard von Weizsäcker on the 40th anniversary of the war’s end - in which he declared 8 May 1945 the “Day of Liberation” - was the first turning point in commemorative politics and policy.

What does it mean to get engaged in a project like “wounds of memory” today?

Although the installation can reveal few profound memories 75 years after the war’s end and 27 years after the project was created, it nonetheless continues to engage its viewers in a dialogue and allows streams of thought to flow together. These scars remain visible. They carry the past with them as sites of remembrance and reflection, where it is possible to explore the traces of history in order to answer questions that are relevant and important to us today.

In January this year, the chair of the Auschwitz Committee in Germany, the Holocaust survivor Esther Bejarano, called for 8 May be declared a national holiday as Liberation Day, because “Sunday speeches that demonstrate concern are not enough," Bejarano wrote in her “open letter to the government and all people who want to learn from history.” “This concern must lead to action; it must be asked how it could have come that far. There has to be a fight for a different, better society without discrimination, persecution, anti-Semitism, antiziganism, without a hatred of foreigners! Not just on memorial days!” Our view of the past comes from the present and leads to the future.

What does it mean to get engaged in a project like “Wounds of Memory” today?

Although the installation can reveal few profound memories 75 years after the war’s end and 27 years after the project was created, it nonetheless continues to engage its viewers in a dialogue and allows streams of thought to flow together. These scars remain visible. They carry the past with them as sites of remembrance and reflection, where it is possible to explore the traces of history in order to answer questions that are relevant and important to us today.

In January this year, the chair of the Auschwitz Committee in Germany, the Holocaust survivor Esther Bejarano, called for 8 May be declared a national holiday as Liberation Day, because “Sunday speeches that demonstrate concern are not enough," Bejarano wrote in her “open letter to the government and all people who want to learn from history.” “This concern must lead to action; it must be asked how it could have come that far. There has to be a fight for a different, better society without discrimination, persecution, anti-Semitism, antiziganism, without a hatred of foreigners! Not just on memorial days!” Our view of the past comes from the present and leads to the future.

Sabine Brantl is Head of History Department at Haus der Kunst. In her capacity as a curator, she is responsible for exhibitions and projects on the history of the institution, archive and memory.